Will AI save endangered languages?

What is being done, what is being said about it, and what is called for. In memory of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

Over at the Brookings Institute’s Tech Tank, Brooke Tanner and Cameron Kerry ask “Can small language models revitalize indigenous languages?” They begin with a discussion of what Small Language Models, or SLMs are; they are like the more well-known Large Language Models—LLMs—of which OpenAI’s ChatGPT may be the most famous, but they require fewer resources to train and run. This includes requiring less data about the target natural language, be it English, Ga, or Guarani Mbya.

It is in the sixth paragraph that Tanner and Kerry do something both interesting and fairly common in discussion of languages that are not widely spoken. Namely, they importantly elide the question of how many speakers various languages have, offering statistics and reflections about one set of not-widely-spoken languages, and then going on to talk about another set of languages that usually has more speakers.

The languages that dominate given African territories tend to accrue to themselves the lion’s share of support, development, and investment.

With Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o having passed away on 28 May 2025, the topic of what he called “mother tongues,” which is always of interest in African Studies, has lately been in particularly spirited discussion online.1 For Ngũgĩ, mother tongues were not merely things. They were tools which gave their bearers power; furthermore, it was the social and political importance of this power, both to ourselves as individuals and to our communities, that meant that we all have certain obligations with regard to our mother tongues.

Ngũgĩ’s ideas about the relationship between languages and power stand out with particular brilliance when supplemented, compared, and contrasted with those of Senegalese academic Cheikh Anta Diop. Weighing these two together can help us make good sense of some of the very exciting work being done in terms of computerized natural language processing. But before doing so can light our way, let’s take a look at the conceptual groups Tanner and Kerry use, and how they relate to current trends in computational linguistics, to get an idea of where things stand now.

Languages: indigenous; rare; and target.

Tanner and Kerry write,

Indigenous languages play a critical role in preserving cultural identity and transmitting unique worldviews, traditions, and knowledge, but at least 40% of the world’s 6,700 languages are currently endangered. [. . .]

Building on the advantages of SLMs, several initiatives have successfully adapted these models specifically for Indigenous languages. Such Indigenous language models (ILMs) represent a subset of SLMs that are designed, trained, and fine-tuned with input from the communities they serve.

UNESCO, on which Tanner and Kerry draw, often describes indigenous languages in subaltern terms.2 That is, UNESCO sees indigenous languages as ones spoken by people who are minorities in their respective countries.3

For their part Tanner and Kerry tie the idea of indigenous languages to the set of declining languages: those that have progressively fewer speakers as time goes on, and specifically those that are in danger of extinction. Thus it seems that the set of indigenous languages, that of endangered languages, and that of those that need “revitalization [] and preservation” have sufficient overlap between them that no further distinctions need to be made.

Ethnologue, a standard source, does not presume that a language’s being indigenous and its being endangered are the same thing:

Language endangerment is a matter of degree. At one end of the scale are languages that are vigorous, and perhaps are even expanding in numbers of speakers or functional areas of use, but nevertheless exist under the shadow of a more dominant language. At the other end are languages that are on the verge of extinction (that is, loss of all individuals who continue to identify the language as being related to their identity). In between are many degrees of greater or lesser vitality.

This is already more nuance than the Brookings piece tackles. There, Tanner and Kerry offer a series of paragraph-long case studies. A careful look at these cases suggests that there may be significant distinctions that should be made between the very different ways of grouping languages implied by the terms “indigenous,” “endangered,” and “supported, revitalized, and preserved,” the last category of which I will call “target languages” of artificial intelligence, in keeping with standard practice. Before getting to Tanner and Kerry’s cases, however, let’s look at the world’s biggest market-based solution for broadening the set of computational language model target languages.

Google’s initiative.

Since 2022, Google has been running the “1000 Languages Initiative.” As Jeff Dean, Chief Scientist of Google DeepMind and Google Research put it in the blog post launching the initiative:

[T]oday we’re announcing the 1,000 Languages Initiative, an ambitious commitment to build an AI model that will support the 1,000 most spoken languages, bringing greater inclusion to billions of people in marginalized communities all around the world. This will be a many years undertaking—some may even call it a moonshot—but we are already making meaningful strides here and see the path clearly.

Dean cites a slightly different number of languages in the world, 7000, than do Tanner and Kerry. This difference, while notable, is not relevant to our purposes; it is the difference between Google’s roughly 1000 languages being the ~14% or the ~16% of the worlds’ languages with the largest population of speakers.4

The endangered languages supported by Google all have thing in common: none of them are spoken primarily in Africa or among its diaspora.

If along the spectrum of language communities, 40% of the world’s languages are in imminent danger of soon having no more speakers at all, and 14% represent Google’s moonshot to maximize its global market cap, 46% are somewhere in the middle. We can be fairly certain, however, that none of Google’s target languages, which are selected because they are very widely spoken, are also endangered. Some of the ones closer to the bottom of Google’s list are likely to be marginalized in the sense that, in the world system, the communities most likely to speak these languages do not have the social and political power currently enjoyed by many in the Global North. This is a very important sense, and Dean is absolutely right to say that they often are marginalized communities. As we go on, however, we will see how there are meaningfully distinct ways in which different language communities around the world can be marginalized.

The African and diaspora languages Google has announced supporting as part of its 1000 Languages Initiative since 2022 are: isiNdebele, isiXhosa; Kinyarwanda; Northern Sotho; Swati; Sesotho; Tswana; Tshivenda; Xitsonga; Afrikaans; Amharic; Swahili; and Zulu;5 Acholi; Afar; Alur; Baoulé; Bemba; Dinka; Dombe; Dyula; Fon; Fulani; Ga; Jamaican Patois; Kanuri; Kiga; Kikongo; Kirundi; Kituba; Luo; Mauritian Creole; Ndau; South Ndebele;6 NKo;7 Nuer; Papiamento; Sango;8 Seychellois Creole; Susu; Swati; Tamazight (both Latin and Tifinagh Script); Tiv; Tumbuka; Venda; and Wolof.9

Google has announced support for several languages with less than one million speakers, and given the distribution of language communities throughout the world, is likely to do so more as time goes on. For the same reason, few in the final set are likely to have less than 500,000 speakers. That said, and despite the terms set out by Dean in the initial announcement, Google has already announced support for a small number of languages with far fewer than 500,000 speakers, including some that are endangered.10 The endangered languages in question all have one thing in common: they are either spoken in Europe, as are Breton and Sámi, or in other G20 countries. None of them are spoken primarily in Africa or among its diaspora.

Facebook’s program.

Tanner and Kerry list a variety of initiatives with relatively less breadth than Google’s efforts, starting with one run by one of Google’s peers. Some of these do target endangered languages. Most do not, but rather target a broader set of “low-resource languages.”

“Low-resource language” is a term of art in the natural language processing field. The first languages on which LLMs were trained, like English, French, and Russian, are known to have sufficient resources to train an Artificial Intelligence model. As an advertisement Google placed in the Atlantic said,

The problem is that an estimated 50 percent of all websites are written in English, and the top 10 languages account for more than 80 percent of all content on the internet. The vast majority of the Earth’s languages are [. . .] “under-resourced languages,” meaning that the mountains of textual data needed to train an LLM in that language don’t exist.

This is like looking at the results of an elite marathon, and categorizing all but the first ten to cross the finish line as “low-speed.”11 Yet this rhetorical elision between what are, for computer programmers, “low-resource languages” and the set of “endangered languages” is very common, especially among popularizers of natural language processing research.

As yet, neither the corporate world nor the public-benefit sector are coming to the rescue of African linguistic communities on the brink of silence.

In June 2024, researchers from Meta published in Nature an article about their company’s No Language Left Behind program,12 which targets 200 languages including both high-resource ones like English and Russian and several dozen that by the end of that month would also be listed among Google’s achieved targets, like Bemba, Dinka, and Kiswahili. Notwithstanding the grandiose, marketing-friendly title of their program, the Meta researchers, like the Google team in its blog posts above, were careful not to make claims in their article that would be impossible to substantiate regarding the relationship between their target language set and the set of the world’s endangered languages. The same is true for the anonymous author or authors of Meta’s digital announcement of the program, which included a discussion of its partnership with the Wikimedia Foundation. Nature’s editors, in an unsigned editorial, felt no such compunction to limit themselves to scientists’ peer-reviewed findings. “Meta’s AI system is a boost to endangered languages” read the headline of Nature’s editorial; “Automated approaches to translation could provide a lifeline to under-resourced languages” read its subhead. In its text:

It’s an important step that helps to close the digital gap between such neglected languages and languages that are more prevalent online, such as English, French and Russian. It could allow speakers of lower-resourced languages to access knowledge online in their first language, and possibly stave off the extinction of these languages by shepherding them into the digital era.

[. . .]

Of the almost 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, about half are considered to be in danger of going extinct.13

Endangered language support efforts.

Tanner and Kerry go on to cite work by Brazilian, Canadian, Indonesian, Norwegian research teams to document languages that are formally endangered, with less than 100,000 speakers worldwide—in some cases, less than 20,000. Of these four countries, the first three are members of the G20, to which Norway holds observer status. These are global economic heavyweights. They are countries whose research communities are relatively well-resourced. They can afford to research things that, in themselves, show little immediate promise of being economical.

The efforts of the other corporate and multinational teams cited by Tanner and Kerry are all focused on languages whose communities, while marginalized, are not endangered. They have millions or tens of millions of speakers. As yet, neither the corporate world nor the multinational public-benefit sector are coming to the rescue of African linguistic communities on the brink of silence.

These distinctions matter because many language populations in the Global South truly are marginalized, even if their languages are not currently endangered. Many of the largest of these are likely to be targeted by Google, Meta, OpenAI, and other for-profit entities. Communities that speak truly endangered languages, if they are resident in wealthy countries with strong traditions of research, may have increasing access to digital preservation tools even as they stand on the precipice of linguistic extinction. Yet other communities are from a corporate standpoint uneconomically small, live in countries that are not able to extensively fund preservationist research, and speak languages that are endangered and are likely to be extinct by the end of the century. Only by recognizing these distinctions can people who care about some or all of these language communities start to articulate a set of priorities for future action.

Two case studies.

I and my family have personal experience with these distinctions. My wife and I both speak languages with less than 100,000 speakers globally; I do not speak the one she does, and she does not speak the one I do; we have other languages in common.

Saamaka, which I speak, is ranked “stable” by Ethnologue. Its community of speakers is too small for it to be of economic importance to a Google, Meta, or OpenAI, but it has a growing online presence. When I die, despite the fact that its speaking population is smaller than that of those targeted by Google and Meta by an order of magnitude, it will likely still be a thriving community even without major preservationist efforts. Beyond the assessment of linguists, I could see this when I was still on social media and would regularly encounter Saamaka being used verbally and in writing on Facebook, TikTok, and WhatsApp, on streets, rivers, and paths, in cities and villages.

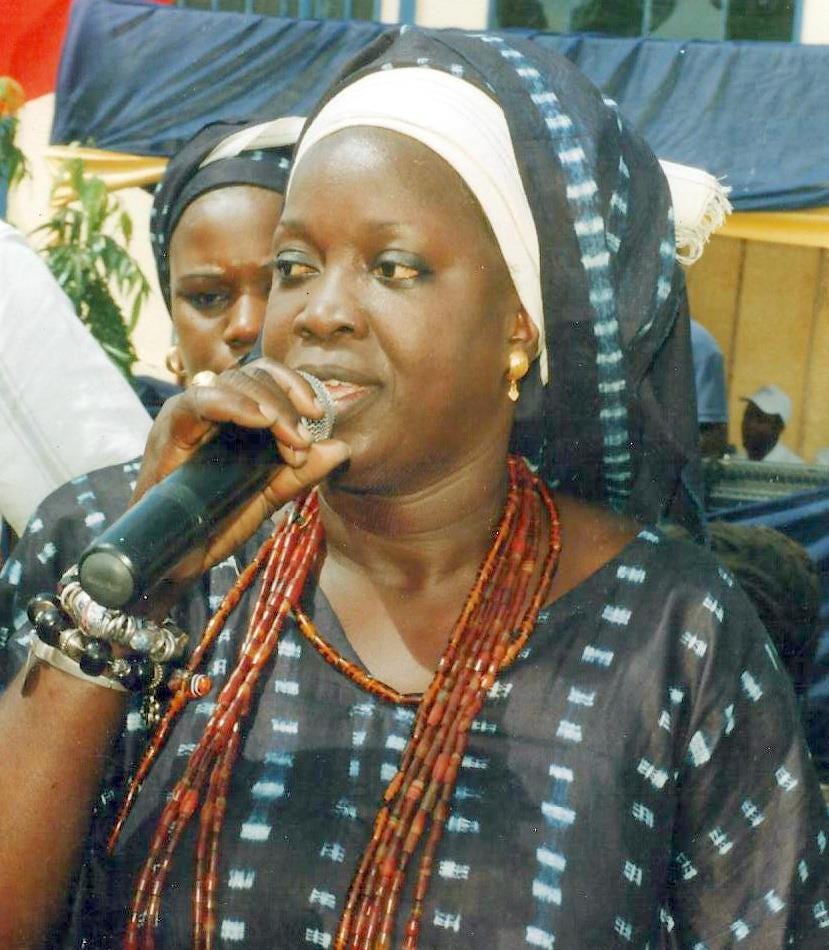

There is much Saamaka collateral, some of it of great historical and cultural importance, that has been produced over time but is not being shifted online, but this does not change the overall picture. By contrast, when my wife and I look on YouTube for videos related to her language, we find digital transfers of thirty-year-old music videos by the enchanting singer Marie Ngone Diome.

My wife speaks Laalaa, a language with fewer than 15,000 speakers globally, of which Glottolog laconically says that it is “[s]eriously threatened and doomed to extinction in the near future.” Laalaa is what Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o would call my wife’s “mother tongue”; linguists would call it her L1. I long used to think that no dictionary had ever been compiled for Laalaa, a statement which is true of many seriously threatened languages. But between the last time I checked and when I started research for this article, it seems that Glottolog had added a new bibliographical reference: in 1981, Walter Pichl, a German linguist who specialized in Cangin languages, the family to which Laalaa belongs, produced a 259-page Laalaa dictionary, in manuscript.

In addition to Laalaa being my wife’s mother tongue, it is also our two-year-old daughter’s mother tongue, but it is not her L1. All of my daughter’s cousins, aunts, and uncles who grew up in the same village as did my wife can speak Laalaa; none of those who grew up in other places can. My wife and I do not expect to be able to make a living in that village, and so do not expect to raise our daughter there. We visit as often as we can, my wife and daughter more than I.

Weep not.

In an excellent profile in the Manchester Guardian from 2023, Carey Baraka puts Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in class with his fellow authors Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, calling Ngũgĩ “the unabashed militant.”14 Baraka, like Ngũgĩ, is Kenyan, but writes in English, a practice which Ngũgĩ otherwise condemns. In their interview, Baraka is able to establish a rapport, and Ngũgĩ expresses admiration that Baraka is able to make a living from his writing. Ngũgĩ notes that he never was. Instead he supported himself in a series of academic posts. Baraka writes,

One Ghanaian playwright, in despair about the seeming impossibility of abandoning English, pointed out that his language, Dagbani, was spoken by a relatively small group of people in Ghana, and if he wrote in it, he would hardly be read. In any case, the infrastructure to publish in his language did not exist. When I mentioned the example of Ngũgĩ, his rebuttal was swift. “Well, Ngũgĩ is Ngũgĩ,” he said. “You can’t compare me to Ngũgĩ.”15

Because Ngũgĩ is sui generis, putting him and his unique record of achievements up against stubborn demographic or economic observations can risk sidelining him; that is not the intent here. Instead, while understanding the unique constellation of challenges and opportunities that being Gĩkũyophone gave him, we can use his pronouncements as an invitation to imagine and struggle to create a less oppressive world, and, though only later, to think about why this question of language death is important even when the remaining speaking community is quite small. In a fascinating interview with Billy Kahora over at Brittle Paper in 2020, Ngũgĩ said:

If you know all the languages of the world, and you don’t know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue or the language of your culture and add to it all the languages of the world, that is empowerment. My books Decolonizing the Mind and Something Torn and New address this issue in detail. Something Torn and New talks about the politics of memory, and language has everything to do with which memory (of body, place, time etc) is dominant at any one time. Colonization always meant and resulted in the planting of the memory of the colonizer on the body, mind and space, of the colonized.

Here, then, is Ngũgĩ’s standard. It is clear and uncompromising, while also being surprisingly hopeful in its statement. There seems to be a gap between this standard and what is possible for the linguistic communities of Dagbani or Laalaa. Should they just give up? The Senegalese polymath Cheikh Anta Diop has a provocative answer.

Operationalizing language policy.

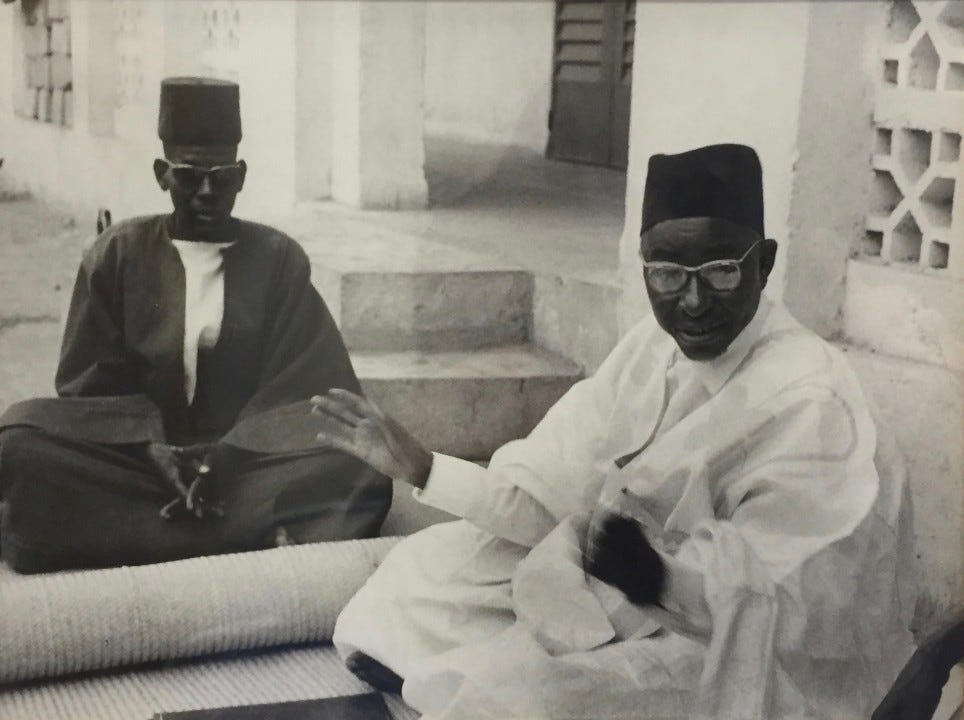

Diop is perhaps most widely remembered as an Egyptologist. Not all the specifics of his theories have held up, but his underlying thesis, that rigorous positivist social science research would reveal the breadth and depth of African history across several millennia, has not been seriously challenged it since he first articulated it in Nations nègres et culture in 1954.

Diop would condense much of the relevant text in his 1960 book Les fondements économiques et culturels d’un état federal d’Afrique noire, which came out one year after he attended the 1959 Rome Congress of Black Artists and Writers. In both books, he places languages into several categories relevant to us:

Cultural Languages: these are languages, like Dagbani or Laalaa, which are porters of cultural meaning. In Nations nègres et culture, Diop is more pointed on the probable fate of many of these languages: like Breton, they may become inconsequential and risk disappearance, being displaced by larger language communities. He says “the multiplicity of African languages is thus a problem [] and one that we can resolve in turn.”

Local Languages: this is the word that Diop uses for any language which is preponderant in any “given territory.” Wolof and Senegal are his chosen examples, and he studies them and their relationship in great detail, pointing out both the linguistic and cultural similarities between Wolof, Sérère, Fulani, and other communities in the country. He makes the controversial argument that little would be lost to people in Senegal in switching to Wolof for most interactions. Diop advocated for conscious efforts to adapt African languages to particular situations in which they may not previously have been employed, like certain academic disciplines.16 To different extents, Botswana with Setswana, the Central African Republic with Sango, and Tanzania with Kiswahili have all followed Diop’s suggestion regarding local language institutionalization since the independence era.

African lingua franca: In 1954, Diop argued that a common language for the whole continent would be unnecessary, noting that neither Europe nor Asia had one. By 1960, he had changed his position, endorsing the Rome Congress’ declaration that Kiswahili should be chosen as a lingua franca for Africa. He was adamant, as would be Ngũgĩ in the years and decades to come, that languages brought to Africa by European colonialism should not be used to this purpose, and saw the selection of Kiswahili as something that could displace the European languages that colonialism had emplanted.

Diop is more hard-nosed than Ngũgĩ about languages which, for millions around Africa, would fall into the category of “cultural languages” or “mother tongues” and not that of “local languages.” Yet Ngũgĩ was more realistic about the attachments people can feel for the ways in which language, culture, and history would overlap. If Ngũgĩ better understands the way people feel, Diop better understands the way they, when taken in aggregate, behave. Furthermore, one of Diop’s imperatives from the eve of African independence can today be restated as a simple observation: that what he calls “local languages,” which are in fact the languages that dominate given African territories, tend to accrue to themselves the lion’s share of support, development, and investment.

Whether or not a country follows Diop’s specific policy platform, he is right when he tells us that without proactive language protection policies, many mother tongues will go extinct.

The shape of language to come.

Where does this mean for Africa in a time of large and small language models? First, while neither Diop in 1954 and 1960, nor the UN experts cited by Tanner and Kerry more recently, could have foreseen the date at which computational linguistics and machine learning would become essential topics in Africa, the advent of this time has not significantly upset their predictions. Languages currently spoken by relatively smaller communities on the continent, from a few dozen to several hundred thousand, are facing probable extinction. Neither Google’s 1000 Language Initiative nor Meta’s No Language Left Behind-200 program are likely to make a significant difference in these trends. They target a segment of the global language spectrum that is at relatively low risk of extinction, even as people in this segment may be in many ways disenfranchised.

Brookings-highlighted programs like Brazil’s work with Guarani Mbya and Nheengatu, Indonesia’s work with the speech of the Orang Rimba, Canada’s work with Mi’kmaq, and Norway’s work with Sámi can be models for Africans looking to digitize their own engagement with support for endangered language communities.

In Colombia, the recent renaissance of Palenquero among Maroons, the descendants of escaped slaves, is a great example of language revitalization that did not rely on AI.17 Palenquero is a great diaspora example of the value that language preservation has beyond social pride: languages are key bearers of historically and scientifically valuable information, not just through the content expressed in them, but also through their very linguistic features; to paraphrase Amadou Hampâté Bâ, a Malian writer who attended the Rome Congress alongside Diop, every time a language dies, it is a library that burns.

As Tanner and Kerry have noted, there have been exciting African initiatives in natural language processing, and these have made large strides going back to 2021. These include Masakhane;18 InkubaLM, Lelapa AI’s SLM;19 and the conference series Deep Learning Indaba. AfriBERTa,20 hosted at the University of Waterloo in Canada, was another early mover in this space. All of these support languages spoken by communities of roughly similar scale as those targeted by Google. Given the age of some of these initiatives, it is worth noting that the direction of influence in language choice runs from them to global powerhouses like Google and Meta.

People interested in African languages and culture should promote LLM and SLM investment separated into three tranches:

A certain amount should come out of the pockets of African and international corporations looking to do digital business on the continent; they should develop multiple LLMs covering many of the same widely-spoken languages, competing with one another on both price and quality.

A certain amount should come variously from governments, African investors and philanthropists, universities and research institutes, and global investors and philanthropists in support of preserving and promoting three types of language communities:

One has the same features as those covered by models produced by for-profit companies like those classed under (1), in part to see if they can build better programs, in part to research and develop pathways that may later be used by such companies, and also in part to see if there are particular ways that corporations’ market orientation shape their language products developed for Africa.

Another is stable languages unlikely ever to be economically of interest to the multinationals investing under point (1).

The final set is at-risk languages on the edge of extinction: the African equivalent of Mi’kmaq.

It is only by recognizing that not all local languages and “low-resource languages” are endangered can researchers, developers, investors, and policymakers make informed decisions about how to deploy resources to best support and invest in Africa’s linguistic and cultural wealth.

See, for a small sampling, the BBC’s obituary; the Continent and Harare Review of Books review of Ngũgĩ’s last book, Decolonizing Language; a brief memoir of Ngũgĩ by Ben Okri in the Manchester Guardian; appreciations in the Continent from several anglophone writers from or with strong ties to the Global South; and an interview with the American Nation conducted shortly before he passed away.

In the Americas, the term “indigenous” can often be a point of pride, denoting rootedness in a hemisphere most of whose residents are descended from people who arrived in the last 400 years. In much of Africa, the term can be assumed to have a negative connotation. When this post refers to “indigenous languages,” it is with an attempt to avoid degradation while also hewing closely to the usage found in relevant sources.

There are different ways of counting languages and also different ways of naming them. In this piece, some languages will be referred to by different names depending on the chosen nomenclature of the people working with them. The paradigmatic exception to this rule will be Kiswahili, which will always be referred to as such here, even when program developers call it Swahili.

Swati or Swazi and Tshivenda or Venda seem to have been announced twice by Google as having been added to their translation slate: first in 2022 and again in 2024. IsiNdembele or South Ndembele may fall into this category as well, depending on the varieties in question. In each case, this may be due to distinctions between text- and speech-based support. See also note 4, above, about language naming conventions.

While not in itself a language, NKo is a script developed in the 1940s by Solomona Kanté for Manding languages, which differ amongst themselves mainly in pronunciation and vocabulary. Google offers distinct support in the Latin script for at least one Manding language: Dyula.

Sango is the only language on this list with less than one million native speakers, though at least five million speak it as a second language, mainly in the Central African Republic, where it is both the official language and a lingua franca.

Ethnologue is in most cases the best source for language communities’ populations. For several years, its full records for all but the 200 most common languages in the world are behind a paywall. Wikipedia, on which this post’s population data draws, usually but not always draws on Ethnologue data, including that which is behind its paywall; Wikipedia’s articles on the world’s languages and language families are cited as a matter of course in major linguistic databases like Glottolog and OLAC.

In 2024, Puseletso Mofokeng of South Africa finished 10th in the Cape Town Marathon, with a time of 2:13:31. Abednico Mashaba, also of South Africa, finished 11th, one minute and thirteen seconds behind Puseletso. 499 of 16501 finishers completed the marathon in under three hours.

The word choice of the Nature editorial team should clarify the extent to which Tanner and Kerry are representative, but not unique, in their logical conflation of “indigenous languages,” “low-resource languages,” and “endangered languages.”

More recently in the Guardian, Nigerian author Helon Habila described Achebe, Soyinka, and Ngũgĩ as “like the legs of the three-legged pot, under African literature, while in the pot was cooking whatever fare the minds of these writers conceived.”

Dagbani is reportedly spoken by over 1,000,000 people and has not yet had digital translation or chat services published on LLMs or SLMs. It would be reasonable to assume that this is apt to change within a decade, given the terms of Google’s 1000 Languages Initiative. Gĩkũyũ or Kikuyu, which Ngũgĩ spoke, is reportedly spoken by nearly 7,000,000 people. It has been supported by Meta’s NLLB program since June 2024.

While he does not explicitly say so, for Diop, a language could be both cultural and local, as is the case for someone who grew up in an ethnic group that speaks a locally predominant language like Wolof.

covering, across multiple projects, several languages, including Amharic, Bambara, Chichewa, Gholmala, Ewe, Fon, Hausa, Igbo, Kinyarwanda, Kiswahili, Luganda, Luo and Dholuo, Mossi, Nigerian Pidgin, Shona, Setswana, Twi, Wolof, Xhosa, Yoruba, and Zulu. Focuses include full natural language processing but more often upstream efforts like part-of-speech tagging and named entity recognition.

covering Hausa, isiZulu, isiXhosa, Kiswahili, and Yoruba.

covering Afaan Oromoo, Amharic, Gahuza, Hausa, Igbo, Kiswahili, Nigerian Pidgin, Somali, Tigrinya, and Yoruba.