Strong state, weak state.

State violence and state services, with examples from Brazil, Liberia, Senegal, and the United States.

The thought leader.

Since roughly the beginning of the year, W. Gyude Moore has been on quite a tear. No other single writer has addressed the current turbulence in international capital flows for development from as many different angles, with the same level of penetrating analysis.

In January, before the United States unilaterally cut the core of its official development assistance, Moore, who rose to prominence serving in the Liberian cabinet during the Ebola crisis, coined the phrase “outsourcing their ambitions” with regard to African states in an opinion piece for Semafor. Once the axe fell, the outsourcing of African ambitions was further dilated upon by Ken Opalo and quoted in the inaugural post here at the Radical Cape Reading Room. Moore later wrote a well-considered essay on the website of Global Neighbors, a European think tank focused on Asian relations, which had named Moore a visiting fellow. In the essay, Moore put the recent American foreign policy moves in the context of a century of great power coordination and competition. In a detailed note published by the U.S.-based Center for Global Development, Moore analyzed the state of and prospects for Africa-China relations, with a particular focus on takeaways from the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, which was the ninth in a series and the first in which China made its commitments in renminbi rather than the global reserve currency: U.S. dollars.

Moore has been looking at development financing from just about all angles except that of an everyday African—and he may well have that angle in the works. His most recent piece, also published at Semafor, argues that the African Development Bank could leverage its position to promote intra-continental trade, infrastructure, onshore industry, and education. In passing, the otherwise curious essay shows Moore to be one of the most intellectually gifted individuals to harbor major political ambitions in many years.

So it was no accident that when Vox’s Dylan Matthews looked for a kicker quote for his article on what a world without American foreign aid might look like, he turned to Moore, who said, “I’ve lived in a weak state [. . .]. All this stuff about shrinking the state—it’s all theoretical. If you live in a state that weak, it frightens you when people say ‘the state is too strong.’”

Now you don’t turn to kickers for nuance; that was not the place to go deep on questions of what makes a state strong or weak. But the matter of what exactly state strength is is a key question, for the Liberia or the United States of today, for their neighbors, and for understanding their histories.

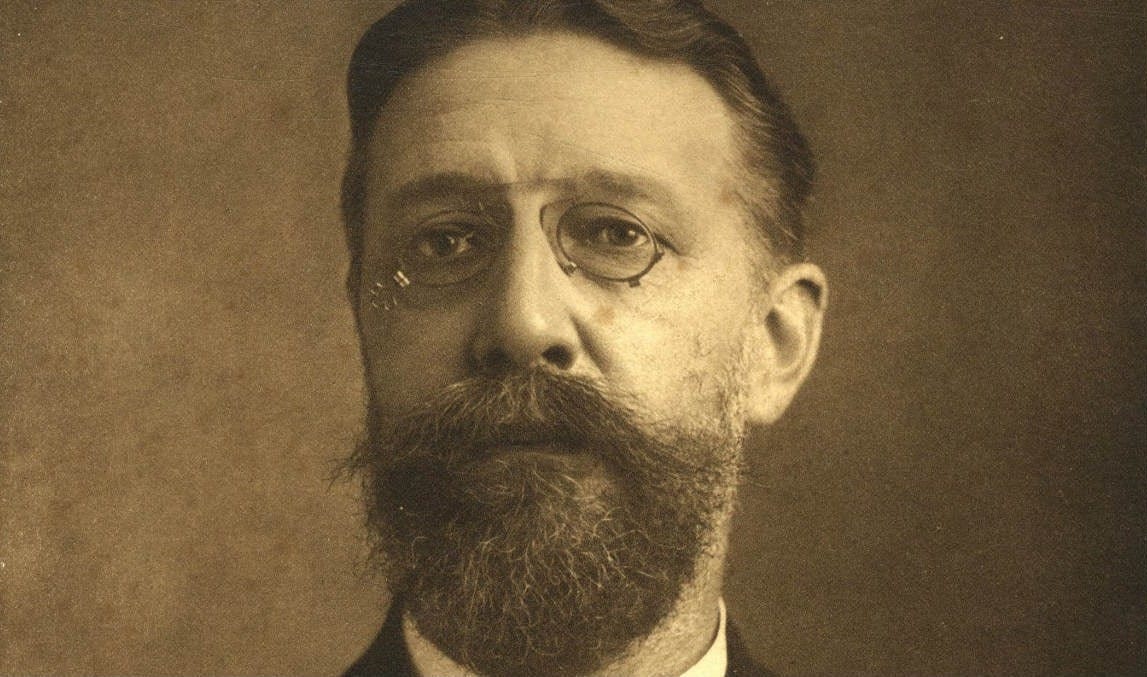

Weber and his audience.

The question of the strength of the state has long rightly been anchored by the functional definition given to states by the sociologist Max Weber at the end of the First World War in his lecture “Politics as a Vocation.” As reprinted in his Essays in Sociology, Weber said, “The state is the human community that successfully claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.” Now, Weber was writing in Europe at what he would have no way of knowing was near to the cataclysmic end of a centuries-long period of protracted interstate warfare—that is, he had no way of knowing that constant succession of European wars would end. His lecture, which rests early on the authority of Leon Trotsky (he was talking at the invitation of a leftist student union), talks about how even the exercise of bureaucratic power depends fundamentally upon the exercise of violence, and then moves on. It is a precept that he sets in place early without expectation of controversy, before going on to investigate in detail how politicians, bureaucrats, and other historical state-adjacent folk go about their business.

Ball of confusion.

The academic literature on the strength and weakness of states has long sought to build on Weber’s definition, and it does take a fair bit of building-on to get from there to where Moore is at when he talks about African states “outsourcing their ambition” to foreigners who give out aid. Clearly this isn’t about outsourcing the ambition to monopolize to legitimate the use of violence—whether, say, Mali expels French soldiers or not, whether or not it welcomes Russian mercenaries, it is still, to a certain extent, acting as arbiter of who may deploy violence within its territory.

No, the “ambitions” in question are the ambitions to govern the provision of goods and services in the territory over which the monopoly of violence are exercised. And it is the matter of how this governance is done that has so confused the literature of strong and weak states that political scientists have produced in the century since Weber’s lecture.

We don’t need to follow all the currents of that confusion. A quick roundabout would look at just two countries: Germany, where Weber gave his lecture, and France, which lost to Germany in the Franco-Prussian War in the early 1870s, and which was part of the alliance which beat Germany in the First World War just before Weber stood up to talk. What Germany found out quickly, and what France soon learned, was that a state’s capacity to mobilize violent action—specifically, its ability to deploy an army that would be victorious on the battlefield—could be augmented if the state mandated certain levels of education and provided certain public services for people who might be conscripted into the military, and for their dependents. Eugen Weber (no relation to Max) spoke in depth about the French effort after its defeat in 1871 to reorganize its citizenship. The so-called Ferry laws, named for Jules Ferry, who rose from French minister for public instruction to the premiership, were a key part of this. In the same decade on the German side, Otto von Bismarck was the first European government leader to pass health, accident, and old age and disability insurance. While not as motivated by great-power rivalry as the French reforms, these improved the health of the industrial and mobilizable populations while decreasing dependency ratios—things intimately tied to the capacity to mobilize violence.

Definition.

We could flesh out Max Weber’s views on violence and the state as being measured along three vectors of strength:

strength with regard to other states;

strength with regard to subjects and citizens;

strength with regard to non-state associations—be these businesses, militias, gatherings, or the like.

The contribution of Ferry and Bismarck to state strength was to make the forces that the state can marshal along these vectors yet more powerful. When Louis Althusser conceptualized schools, whether directly run by the government or not, as collectively the most important ideological state apparatus, he may well have been right. He certainly was very mid-twentieth-century French. And while we can get all the way to what Moore is talking about by adding “strength in providing goods and services” as an enabling fourth bullet to Weber’s core three, it is worth taking a paragraph to dispose of a voluminous bit of the literature that wanders around other matters.

The strong and their deals.

With many theorists writing in wealthy democracies, questions of government legitimacy frequently play into discussions of the strength of states; according to such analyses, democracies often get rated as more legitimate, as do states whose governments recognize certain rights and liberties among their citizens and subjects. Lately, things like economic performance and government regulation of the economy also get added to the equation. The World Bank and the OECD are particularly fond of such frameworks. But this builds in a tension, since without the liberal-democratic angle, it would be presumed that strong states could often be seen to behave in violent or nearly violent ways. With the requirement, violence counterintuitively would seem to be a tool of weak states. Francis Fukuyama, who has for several decades been interested in the rule of law and political order, has addressed this challenge by separating the strength of the state from its scope. This seems to be a useful distinction whether or not it is worth following Fukuyama to all of the conclusions he draws from it.

We can see the implications of strength and scope clearly in the case of the United States. America is capable of bundling people onto planes and deporting them; it is capable of detaining people for decades without trial; it is capable of closely surveilling otherwise private communications; it is capable of assassinating people anywhere in the world. The deal that it makes with most of its citizens and with allied states is that it will generally not use these powers against them. This is what makes it a typical instance of what Daron Acemoglu has called the “consensually strong state” (PDF). Even as it spares most of its citizens, the consensually strong state regularly exercises exactly these capacities—in America’s case, doing so with particular gusto, publicity, and public opposition when one political party occupies its executive. The United States promises its citizens and allies to limit the scope of its most violent and coercive activities to foreigners, suspects, and enemies. The state gets popular and allied support for building up its own overweening strength in part as a result of the deals it makes about when not to act strongly. Such deals are not universal; sometimes they are explicit, and sometimes only implicit. Their terms may rapidly change, as they seem to have done in 2025. Even before that, Africans and afro-descendant populations were among the most affected by American immigration and deportation policies. When resident in the United States, the same populations are also affected by how the country treats its suspects given the criminalization and racialization (PDF) of poverty in that country.

Liberia, overpowered and overpowering.

In Africa itself, we can see states being strong along one vector but weak along another: take Liberia. Between the Berlin Conference in 1885 and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Liberia was weak in comparison with its two neighbors—imperial Britain and France. They exploited this weakness by taking territory which Liberia had already claimed. After the First World War, Liberia’s weakness in the international state system was illustrated by the extent to which the colonial powers ganged up on it in the League of Nations, investigating and humiliating it for practices which were exploitative, but of which the colonial powers were equally guilty.

If the Liberian state was weak in comparison with other states, it was also weak in comparison with associations, as illustrated by the exploitative deal that the Firestone corporation negotiated to set up rubber plantations in the 1920s, which simultaneously plunged the government into debt, and enabled Firestone to expropriate vast swaths of territory, put people to work on it at exploitative wages, and make hefty profits.

Yet even as it was weak as relates to other states and to multinational corporations, the Liberian state of the early twentieth century was also strong, terribly strong, as relates to the people within its borders. While members of the Americo-Liberian ethnic group that dominated politics tended to be “consensually” governed, to use Acemoglu’s term, other Liberians were treated as a subject people. The fiscal, governance, and labor degradations described in the League of Nations report were real, and it is only a slight mitigation to note that the Belgians, British, French, Italians, Portuguese, and Spanish were doing the same things elsewhere in Africa at the same time. Liberia enforced expropriative hut and head taxes, criminalized debt, permitted the use of child labor by its political upper class, and trafficked its own people to labor camps on the island of Bioko, then known as Fernando Po, part of the Spanish Guinea colony. It was that trafficking to Fernando Po that kicked off the investigation that led to the filing of the Christy Report at the League of Nations, which in turn led to the resignation of the Liberian president in 1930.

In the post-independence period, this exact pattern—states that are weak when it comes to other states and as relates to associations such as corporations or rebel movements, but strong as relates to their own citizens—became the norm across Africa. The common coincidence of the two weak prongs even led to a particular theory being put forward: that African countries are merely “juridical states” (PDF). That is, they met the requirements for statehood imposed by contemporary international law, but at the same time, they failed the empirical tests of statehood suggested by Weber: they failed to exercise a monopoly on violent action within their territory.

This is as true in the early 21st century as it had been in the 20th. In the 2010s, the Nigerian state that was too weak to defeat Boko Haram in the north was so strong in its relationship with individual citizens that the government’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) regularly exploited and even killed innocent young and marginal populations in the south. A novel association—a lengthy, coordinated, and uncompromising popular movement to #EndSARS that gained strength domestically and in the Nigerian diaspora at the end of the decade—was able to force Nigeria to shutter the agency in 2020.

Looking back: do the rich get richer, and the poor poorer?

Starting roughly in the 1960s in Latin America and North Africa, where many states had been politically independent of European powers for relatively longer than their contemporaries in Africa, several thinkers were looking at the patterns of state development.1 Perhaps the most advanced node of such thought was among Brazilians either associated with or reacting against work being done at the Chile-based Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, or CEPAL. Celso Furtado to a certain extent kicked off the conversation by looking at the reasons that a country like Brazil might be not just “developing,” as the preferred term of art would then have it, but rather be “underdeveloped.”

Furtado was launching off the work of a CEPAL colleague: what is known as the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, which draws on historical price studies to suggest that over time, the terms of bilateral trade between a rich and a poor country tend to alter to the benefit of the rich one, and to the detriment of the poor. What underdeveloped states could do to improve their lot and that of their citizens was Furtado’s focus; he argued that an underdeveloped state could make use of Keynesian policies available to stimulate industry and capital exchange and counter this effect.

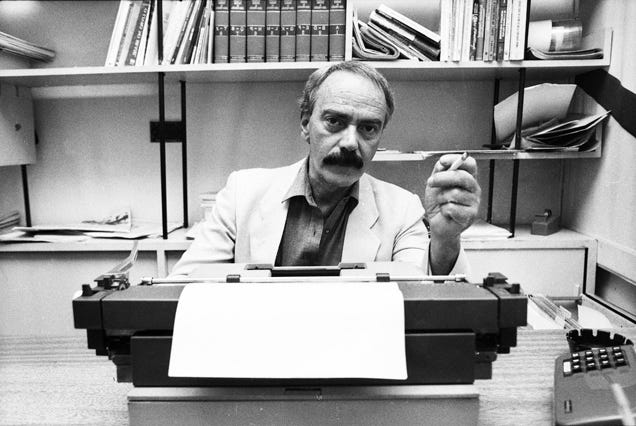

In the United States, the economist and sociologist André Gunder Frank followed CEPAL debates closely and argued that underdevelopment in Latin America should not be understood as a transitory stage of the economic development of states, precisely because it was produced by the same processes that enrichened countries like the United States and former colonial powers.

The idea that exploitation begets exploitation.

Ruy Mauro Marini, whose theoretic approach was influenced by revolutionary Marxism, built on Frank’s model and broke with Furtado and the CEPAL crowd. Marini argued that the international economic system that caused “developed” states to be far more wealthy than “underdeveloped” ones also made it so that workers in underdeveloped states tended, as time went on, to be not just exploited, but “overexploited.” That is to say, the international economy pushes the most extreme forms of economic exploitation to countries of the Global South. This can be thought of as a more formal elaboration of the sentiment contained in George Orwell’s caustic 1939 remark, “What we always forget is that the overwhelming bulk of the British proletariat does not live in Britain, but in Asia and Africa. It is not in Hitler's power, for instance, to make a penny an hour a normal industrial wage; it is perfectly normal in India, and we [the British] are at great pains to keep it so.”2

Marini’s far-left political convictions kept him out of multilateral institutions like CEPAL and out of the Brazilian government; he spent the years of Brazil’s military dictatorship in exile, and much of his work is only now making it into English. His idea that underdeveloped countries, as they developed, would tend to become “sub-imperial” was little influential at the time, though, thanks to the recent translation of one of his key books into English, it is being used right now as a novel analytical frame for the recent rapid growth of the United Arab Emirates’ power in Africa.

Regardless of the lack of immediate influence to the Marinian approach, dependency theory overall did not need to wait as long as he did to reach African shores. In 1970, the Franco-Egyptian political economist Samir Amin brought structuralism back in, this time in written French and addressing global scale. In front of a relatively smaller reading public, Marini’s longtime thought-partner Theotônio dos Santos was doing a very similar thing back in Brazil.

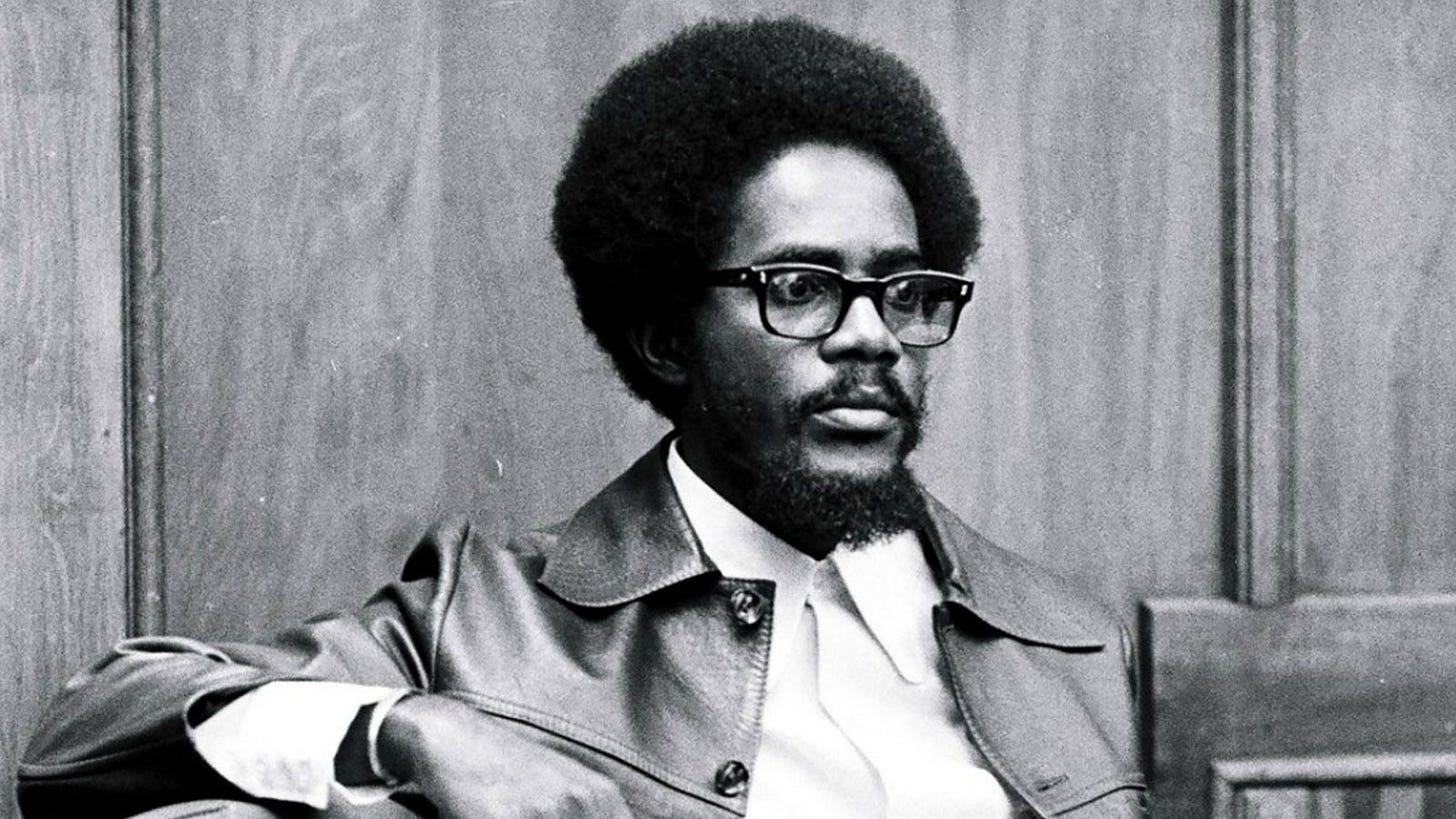

When the Guyanese theorist Walter Rodney wrote How Europe Underdeveloped Africa while at the University of Dar Es Salaam in the mid-’70s, it was on Frank and Amir rather than on any of the Brazilians that he leaned for his conceptual frame. By the 1980s, between Frank, Rodney, and the American sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, dependency theory had definitively entered anglophone discourse.

The reformists, taking power.

Meanwhile, the reformist wing of lusophone dependency theory was active in responding to Marini and his colleagues. In anglophone circles, their publications would often be treated as subsidiary to Wallerstein’s because these wasn’t translated into English until 1979, five years after the publication of the first volume of Wallerstein’s Modern World System. Yet Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto’s book on dependency theory, drafted at CEPAL, had appeared in Spanish in 1969 and in Portuguese shortly thereafter. As was to be expected given their affiliations, they were more optimistic than the revolutionary Marxist theorists. They would be more politically influential, too.

Cardoso and Faletto extended Furtado’s insistence that underdeveloped states could follow a slate of economic policies which would allow them to achieve a slice of meaningful development. Fernando Cardoso’s subsequent career saw him live out both sides of moderate dependency theory. The good side came first. The Brazilian military dictatorship fell, and he was elected president at the head of a center-right coalition in 1995, enacting highly popular cash transfer and pro-industry policies. Then global economic headwinds originating in a small valley in the state of California tanked the Brazilian economy, and Cardoso was rendered unpopular domestically as he struggled to assemble the votes needed to further advance his policy platform. When his second term in office ended, Cardoso became an early and vocal leader of the initially ineffectual opposition to the Workers’ Party of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who governed from Cardoso’s left.

Dependency theory and state strength in contemporary Africa.

Even today, when we see Bassirou Diomaye Faye argue for the renegotiation of contracts with multilateral companies working in Senegal, or the ruling junta in Mali imprison the leadership of a multinational mining firm in order to extract multi-million-dollar payments, what we are seeing is actions fundamentally informed by the idea that the world economic system is, in the absence of proactive government policies, stacked in favor of profits being extracted from the Global South to the benefit of economic centers in the Global North. Similarly, when Gyude Moore promotes African-financed trade, infrastructure, and industry, he is promoting an essentially Cardosian model of development possibility.

Mali’s approach quite literally rests on an attempt to shift the historic capacity of the state to exert violence against certain powerful associations, at the same time as the country deals with chronic insurrections that continue to challenge its monopoly of violence in the north and along its borders. Senegal’s case is closer to the Weberian ideal, in which the notion of violent action is to a certain extent implied to any observer familiar with the context of the country and its neighbors. Yet in this Senegalese case, violence is not used or explicitly threatened. Finally, Moore’s suggestions for the African Development Bank sit at a sufficient distance from any real or implied use of force that it can seem that the question of states and monopolies of violence is very remote from his policy platform indeed.

Yet it is Moore himself who reminds us, in his quote over at Vox, that the question of state power is never too far away: “if you live in a state that weak, it frightens you when people say, ‘the state is too strong.’” Here in Senegal, two consecutive administrations have negotiated formal ends to the low-level insurgency that has troubled the Casamance region since 1982. The Senegalese state is slowly but surely getting ever stronger along the vector that relates to militias, corporations, and other associations.

As seen with health and education outcomes, Senegal is also improving its strength in terms of guaranteeing the provision of goods and services to its citizens. Thinking about strong states along this fourth vector, the strength to provide for citizens and associations, is often more exciting and rewarding than thinking about states’ most nakedly violent coercive power over each other, over associations, and over citizens. But countries advance or regress along each vector of state strength unequally, even though movement along any one vector correlates with that along another. Whether in Liberia, Brazil, the UAE, Senegal, or farther abroad, a single state might be too strong in one area, and not strong enough in another.

Note that all dates in this and the following sections suggest a slower process of exchange than really took place, since they relate mainly to the publication of books by people who were writing articles and drafting chapters every few months, and in many cases having in-person discussions with one another.

This would equal INR 26 in 2025, when the state-mandated minimum wage for unskilled workers in the state of Rajasthan was INR 36 per hour under the assumption of an eight-hour workday. Rajasthan is not representative of the contemporary Indian mean, but rather the extreme: it has one of the lowest minimum wage scales in the country, which as a whole qualifies as middle-income.