To begin with, a geographic note: this is about the part of Africa that, with apologies to geographers, we all tend to call “the Sahel.” Physical geographers tend to draw the border between the two along a line called an isohyet, in this case, one denoting 600mm of rainfall per year, with the Sahel, to the north, receiving less, and the Sudanian Savannah, to the south, receiving more.1

There was a time that any written discussion of human communities would start with a discussion of physical geography. With the increasing trend of the food most people eat being transported across great distances before it gets eaten, this practice has fallen by the wayside. As we think historically about the Western Sudanian Savannah,2 the people who live there, and some of the contemporary trends around conflict, that geographical frame becomes useful. This is true whether the historical span we are considering covers a matter of years, or one of millennia.3

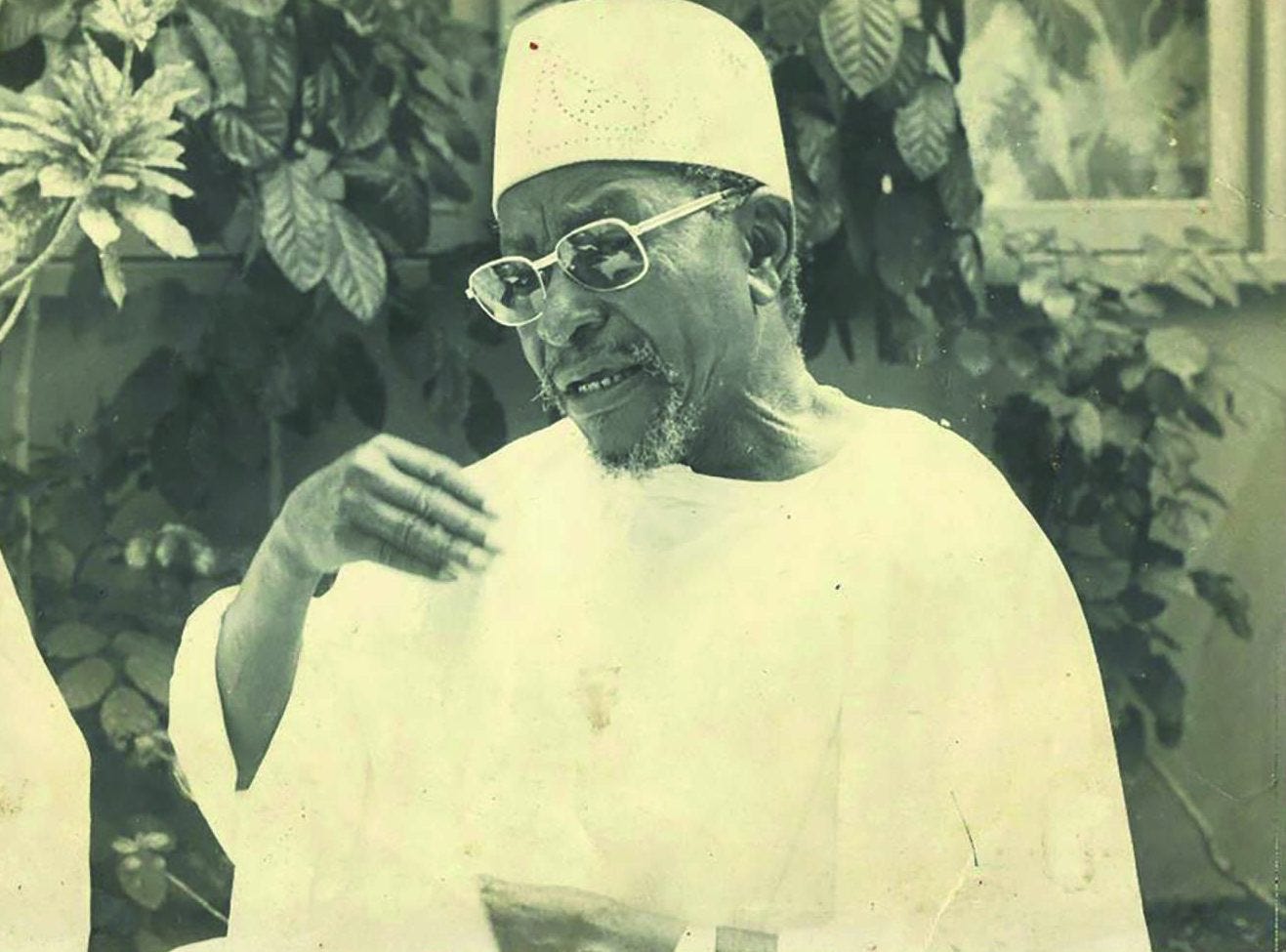

One note before jumping in: Ali Mazrui warns us about the Scylla and Charybdis of what he calls Romantic Gloriana and Romantic Primitivism when it comes to recalling Africa’s past.4 Then, intersecting with that challenge is that of not going too far in the direction of either Afro-pessimism or Afro-optimism. Speaking as it does about armed conflict and proto-state structures, this piece does risk spending a little more time on the side of both pessimism and primitivism than I would normally like to do on balance. I ask readers to trust that, even as this particular picture zooms into challenges, that our mutual awareness of opportunities be not forgotten.

I. Climate change and land use.

The aridification of the Sahara, the Sahel, and the Savannah has been a key trend in the history of West Africa, with the progressive southward march of isohyets in previous millennia being matched by waves of population movements felt as far away as the Bight of Benin. To this day, there are places in Mauritania with Serer names, even though the northern bound of the main Serer homelands has been south of the Cape Vert peninsula for centuries, separated from Mauritania by areas populated largely by the Wolof and the Fulani.

Peer Schouten and James Barnett speak advisedly in a brief report for the Danish Institute for International Studies of “the enclosure of the bush” as they write, “Nigeria has the highest consistent rate of cropland expansion in Africa.”5 While they do not address the rapid demographic growth of the region, this is something that joins northern Nigeria with Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger as countries where land is viewed by its human occupants as an increasingly scarce, rival, and valuable resource. Their whole report is a must-read on the forces at play since the 1980s.

II. Ethnic identities and linguistic influence.

The Fulani speak Fulfulde, a Western Atlantic language, closely related to Serer and Wolof. The Serer, Wolof, Fulani, and related groups lived in close quarters for so long that vocabulary, syntax, and social identity passed from one group to another in bidirectional exchange over the course of centuries.

Cultural identity is also complex. The historian Oumar Kane identifies groups seemingly of clear Serer, Wolof, and Soninke descent in the area called Fuuta Tooro who in the twentieth century spoke Fulfulde as their mother tongue and identified fully as Fulani.6 Other Soninke, settling in the area after 1790, did not socially or culturally assimilate into Fulani culture.7

There is also a large ethnic group, the Toucouleur, who speak Fulfulde but do not identify as Fulani. While the Fulani are linguistically and culturally more closely related to the Serer than they are to the Wolof, the Toucouleur and the Serer acknowledge having closer historical ties with one another than either have with the Fulani, notwithstanding the linguistic and cultural ties between the Toucouleur and the Fulani.8

Overall, there is thus a cultural unity to much, though not all, of Fuuta Tooro, which combines with the tendency of non-Fulani peoples there, especially Toucouleur, to speak Fulfulde, and the Senegalese relative disinclination both to conflict and to using ethnicity as a point of division and conflict—I say “relative,” in comparison with some notable instances farther east across the Savannah.

Fuuta Tooro can seem very different from other Fulani geographies, especially given some terminological features of how Fulani and Fulfulde are described there. Whereas just about everywhere else Fulani people live, their ethnonym is derived from the plural form of the Fulfulde word for “man” (fulɓe), in Senegal and Mauritania, the most common ethnonym is derived from the singular form (pullo).

Even here, it is not too different. If in Senegal, the Fulani are mostly known as Peul, Peulh, or Pulaar, that is because these are exonyms derived from the way Fulani people are called by their neighbors—in this case, the Wolof.9 The names “Fula” and “Fulani” are also exonyms—in this case, words in Mande languages. Hausa looks both west and east, using both the Mande and the Chadian Arabic term: variations on “Fulata.”10

Everywhere where Fulani people live, they are apt to use calques and loanwords from neighboring languages—mostly the Atlantic group in Senegal, Mande languages in Mali, Gur languages in Burkina Faso, and Hausa and Kanuri11 in Niger and Nigeria. Sometimes, as we will see, these adaptations and borrowings filter back into their source communities, as if new. Sometimes, non-Fulani people are willingly or unwillingly “fulanized.” And sometimes, local trends that may have obtained whether or not there were any Fulani around get attributed to the Fulani.12

Alliances and joking relationships between the Fulani and other ethnic groups are not limited to Senegal; Maurice Bazémo catalogues similar relationships with the Bobo, Fulse, Gurma, and Marka peoples in Burkina Faso.13

The fact that there are commonalities across the Savannah, and the fact that one of these commonalities is the frequent participation as victims or aggressors of Fulani group-members means that looking at Fulani across time and space is a great way to understand the Savannah conflict continuum. Still, not everyone in an insurgent or bandit group is Fulani; not even all leaders are. Peer Schouten and James Barnett write in a lengthy report for the Danish Institute for International Studies, “gangs may be joined or led by Hausa or other ethnic groups,” noting, “Jan Kare, Dan Karami Alhaji Kundu and Dan Dela are all notorious non-Fulani bandit leaders.”14

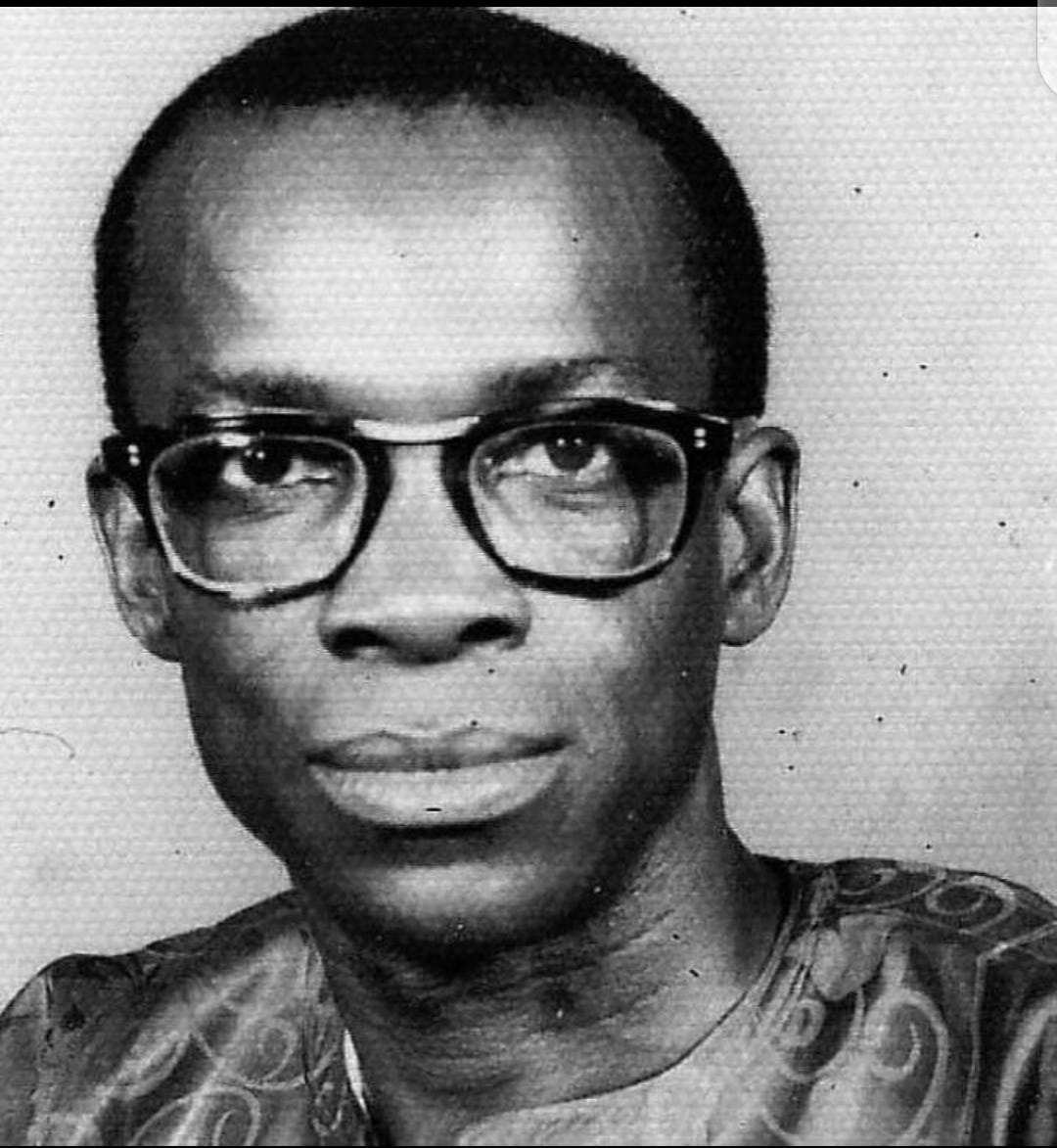

According to the Malian anthropologist Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Fulfulde separates Fulani geographies into three categories: Fuuta Kiiɗndi, Fuuta Keyri, and Fuuta Jula.15 The Fuuta Kiiɗndi is the Old Territory, comprising the Fuuta Sahel, in what is now southeast Mauritania, and Fuuta Tooro, in the valley of the Senegal River. Fuuta Keyri, or the New Territory, consists of Fuuta Jallon in what is now Guinea-Conakry, the former Massina Empire in Mali, the Sokoto Caliphate in Nigeria, and the chieftaincies of northern Cameroon. Fuuta Jula, or the Trading Territory, is anywhere else Fulani people may live.

You may notice that other than using words like “caliphate,” I don’t talk much about Islam in this post. That is not by accident. While many armed groups across the Savannah express strong religious motivations for their actions, the most fundamental underlying drivers are not faith-based. Thus, in 2019, Mathieu Pellerin wrote in an English-language report for the French Institute for International Relations, or IFRI, that in West African “the formation of insurgency dynamics [] the religious dimension—in any event initially—is quite minor.”16 In this he was drawing on what he called “unanimous” agreement in the “[e]xisting literature.”17 Later in the same report, he cautions that “it would be rash to assume that these actors are always driven by non-religious motivations.”18 Religious language and logic can assume major localized importance in these conflicts, sprouting out of a space that is not in and of itself religious.

III. Communities domesticate.

In the first section, we talked about how the desertification of the Sahara and the aridification of the Sahel led to population movements felt as far away as the Bight of Benin. Well, by the fifteenth century, the kola nut was discovered in the forests of what is now Ghana by the Asanti. A whole host of mainly Hausa settlements sprang up along the route from Gonja in Ghana to Kano in Northern Nigeria as the region’s economic engine shifted from agriculture to mercantilism.19 In Borgu, a state whose territory fell between what is now northern Benin and northwest Nigeria, a host of princes known as Wasangari sprang up; Nigerian historian Olayemi Akinwumi models them as falling into two groups: the fortunate and the unfortunate. He writes of “the less privileged Wasangari”:

They were, in most cases, those who lost out in political contest for the control of the political stools and those who were not directly connected to the incumbency in Borguland. They became warlords robbing the caravan merchants of their goods, raiding the Fulani of the cattle and abducting and selling the peasants into slavery. Not only that, as warlords, they offered their services to the caravan traders, for a price, as security guards on the routes through Borgu.20

Sometimes, he writes, they “even captured the traders themselves and later sold them into slavery.”21 Drawing on Eric Hobsbawm’s concept of “social bandits,”22Akinwumi writes that this warlordism developed out of an extensive decentralized practice of “banditry” that began among the ethnically diverse population of the region in the fifteenth century, well before the growth of sedentary Fulani states in the region; it grew over time along with the interstate trade which fed it, and reached its peak in the nineteenth century, when Usman Dan Fodio founded the Hausa-speaking Fulani Sokoto Caliphate at the point along the Gonja-Kano route where it crossed northbound trade from Badagry—what is now Lagos, where Europeans were offloading goods in exchange for African raw materials.23

Schouten and Barnett write, “Over the past decade, bandits have systematically stripped rural farmers and herders of their livestock, allegedly transforming themselves into the region’s largest cattle owners.”24

In their brief report, they underline the extent to which, under a banditry regime, regional economies “work” even worse than they had before for most local residents.25 Yet the cadres of these protostates garner enough financial throughput and social capital that they, who exert the preponderance of the local capacity to inflict violence, have little incentive to give up their approach.

IV. Communities reproduce.

A key part of community reproduction is the production of an ideology contextualizing and justifying the community’s behavior. That is to say, an ideology produced or adopted and accepted by the community itself. For Savannah communities that elect into violent jihad, groups like al Qaeda and the Islamic State offer ready-made ideologies that can be adapted. But even violent jihadist ideologies wind up being reshaped and re-rooted into the local context. Samba Dieng describes how partisans and opponents of the Toucouleur Empire which succeeded the Massina Empire in the upper Niger River region developed rival epic traditions which, over time, tended to coalesce with one another on the most essential matters.26

Many of today’s finest researchers use participatory methods to build out their studies when they have the time and resources to do so. With the tight focus that often exists, rightly so, on the fighting and displacement attendant on the current conflict, relevant cultural reproduction also occurs far from the firearms and motorbikes. If Samba Dieng recorded the traditions which recounted and justified the actions of El Hajj Omar Tall, back in Jolof and Ferlo, two parts of Senegal just immediately south of the Senegal River and Fuuta Tooro, Moussa Diallo highlights examples of sustained cultural production for peace. These prosodic traditions focus not on war, but on pastoral27 and largely pacific religious topics.28 Farther east, Amadou Hampâté Bâ documents oral traditions that are many centuries old yet in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries continue to be transmitted even through religious conversions, wars, colonization, expropriation, and population displacements.29

Maurice Bazémo writes that Fulani noble refugees fleeing Massina after 1840 came to what is now north and west Burkina Faso and started conducting razzias, nominally in the name of jihad, to win converts to Islam, but more to enslave people both for their own service and for sale onward toward North Africa. Connections to this latter market offered the free nobles of the Savannah opportunities to increase their own wealth. Bazémo notes that the Fulfulde concept of pulaako, the upstanding behavior of members of the Fulani noble caste, was largely the same as that of burkina for the Mossi: it was an unvanquishable chivalric quality that members of the uppermost cadre of a slave-holding society recognized among members of the same cadre of their own ethnic group, rendering the enslavement of such people unthinkable. Razzias were meant to enslave outsiders, and the low-born.30 Yet if the nineteenth-century Fulani were for Bazémo the index case of an enslaving society in Burkina, they were far from being the most significant, and he goes into great detail on how many of the innovations in terms of promoting unfreedom which some Fulani can be understood to have introduced to Burkina were eagerly taken up and adapted by other peoples.

In what is now Nigeria, Usman Dan Fodio, who founded the Sokoto Caliphate in 1804, was as successful as he was because he, in the words of French historian Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, “appeared as a liberator simultaneously to peasants and to literate Muslims.”31 To this point it is useful to hold in counterpoint an article by Paul Lovejoy on the role of forced concubinage in the expansion of the Sokoto Caliphate in the nineteenth century. Before delving into the role that such unions played in the demographic expansion of the ruling elite, Lovejoy notes that marital slavery continued as a minoritarian practice in Northwest Nigeria well through the late twentieth century.32

While slavery and forced marriage rightly get significant attention when they occur, I am interested in reading more about the extent to which, if at all, the Savannah conflicts that we see are fueled by attempts either to transcend or to benefit from pre-existing systems of unfreedom. This may include individuals’ current or former status of enslavement, their lineal descent from enslaved people, or appurtenance to a low-status caste. Any one of these may significantly affect individuals’ ability to make a life for themselves and their family, to engage in a marriage of their choice, and other behaviors that are highly relevant to the questions of freedom and autonomy that have lately driven conflict in the Savanah.

To this day, the best discussion of the interrelationship between caste, freedom and enslavement, and social reproduction in a Savannah context is Abdoulaye Bara Diop’s study of the Wolof of Senegal. Diop outlines a matrix very similar to that found in other West Savannah societies, though the picture he paints brings us only up to the age of independence.33

I can’t wait to read an update, especially, in the context of this post, one focused on today’s conflict geographies. Among think-tank analysts, James Courtright of the Clingendael Institute may have gone the furthest so far this direction, as when he writes:

[E]xternal shocks to pastoral livelihoods were accompanied by shifting power dynamics within different Fulani societies. In the lush inner delta of the Niger river—a unique ecosystem in central Mali that can support large herds of livestock during the punishing eight-month dry season—semi-nomadic herders began to chafe at the increasingly exorbitant fees paid to hereditary Fulani land owners in the 1980s and 1990s. At the same time, in central Nigeria, decades of southward migratory drift by herders led to disputes between newer Fulani arrivals and the Fulani herders who had been visiting these areas for generations. In some places, groups of pastoralists felt abandoned when the settled and urbanized Fulani elites, who they previously relied on in times of need, became part of the government and rebuffed their calls for support. Meanwhile, somewhat tangentially, former Fulani slaves [. . .] in parts of central Mali and northern Burkina Faso were challenging their subservient position in society in disputes over land and access to local political power. Thus, although specific dynamics differ, pastoralists across the region—who had often previously held privileged positions in the social order—felt squeezed not just by governments and farming communities, but also by other Fulani.

In the early 2010s, the crisis in pastoralism reached a critical point in both the central Sahel and Nigeria. In the central Sahel, the resumption of the Tuareg secessionist struggle in northern Mali in 2012 ignited tensions between and within pastoralist societies. Fulani pastoralists—watching their Tuareg rivals join the Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad—sent their sons to join the jihadist group [. . .].34

V. Powers and the protostate continuum.

Michael DeAngelo, now of the American Enterprise Institute, made a very useful point in a March article about the largest jihadist groups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger for the Foreign Policy Research Institute. Namely that these groups, which were at first conceptualized as terrorist groups because of the distribution of their early activities and the relationships they and their predecessor groups had with al Qaeda, should instead be thought of as insurgencies.

Fulani in what is now Mali and norther and western Burkina Faso have a strong recent history of structural advancement in state development, though their enemies might also take consolation in the fact that the longest-lived of these states did not survive three full generations. That state, the Massina Empire, had a complex and interlocking counter-checking administrative apparatus with fallback systems covering governance, executive and local administration with populometry, the investigation and control of corruption, judicial trial and review, police and military power, education, and religious exercise with considerations for both believers and non-believers.35 It did take decades to get to that level of sophistication, however. Some of the systems pre-existed the foundation of Massina; others were elaborated over time. While Massina’s leadership was sedentary, fixed in Hamdallay, one of its earliest activities was to settle a month-by-month, multi-year plan for which pastoralists were directly and indirectly responsible for pasturing and watering which herds where in their territory.36

Ok, so the Massina Empire was definitely a state. But especially looking at what’s going on in northwest Nigeria, should we really consider that in the same category? I would say, yes, for several reasons.

Among the three “dynamic[s] of engagement in jihadist groups” identified by Pellerin is “that of actors acting as mercenaries for the benefit of jihadist groups.” He goes on:

They may be bandits, traffickers, poachers, or private individuals seeking gainful employment. Depending on the contenxt, these actors, whose material interests would have been undermined by the authorities, share an opposition to them with the jihadist groups. [. . .] The most common trajectory throught the Sahel is that of armed bandits who ally with or join jihadist groups. [. . .] In eastern Burkina, many former bandits—probably more than before—have joined the jihadist groups. This specific feature is due to the fact that the eastern region has for a long time been the main center of banditry in the country, until the Koglweogo largely stopped their criminal activities in 2015 and 2016. So, made unemployed, many of them sought the support jihadist groups to wreck revenge on their former persecutors.37

These Koglweogo are key to understanding historical dynamics specifically in Burkina and more broadly across the Savannah. They were militias.38 Pellerin wrote of their relationship to jihadi violence:

In Burkina-Faso, faced with the development of the Koglweogo, that are mainly Mossis, the Fulani communities also sought to arm themselves, initially by joining the Koglweogo in their turn, before organizing around the Rouggas [people chosen by the pastoralists to manage the safety of herds].39 But, since the start of 2019 and the increase in operations by the Koglweogo targeting the Fulani community, these groups have not been enough and joining jihadist groups has been necessary as a last resort solution. This alignment is often limited to passive complicity or to circumstantial alliances. When it is not protection, many turn to these groups for the sale of revenge: revenge against these self-defense groups or against the states after their defense and security forces have used disproportionate violence.40

We’ll get into the subsequent evolution of Koglweogo in section seven. For now, even here, we can see the increasing complexity and organization of many erstwhile “bandits” in eastern Burkina toward the end of the 2010s, from individuals and small teams through militias and into membership in jihadist groups.

In 2021, James Barnett and Murtala Rufai called northwest Nigeria “the other insurgency,” bemoaning the fact that “the militancy [there] does not fit neatly within any of the paradigms through which Western observers generally frame African conflicts.”

Recent research from Nigeria suggests that it is not necessary for banditry to transform fully into jihadist violence in order for it to take on insurgent protostate form, though that was precisely the worry that animated Pellerin in 2019.41

Bandits in northwest Nigeria, in addition to extracting rents from subject populations, have also been negotiating what Obi Anyakide calls “peace deals” in a 2023 article in the New Humanitarian.

The leaders of bandit groups in the region are known as “kachalla.” Voice of America says that kachalla is a Fulani word, and while it may be used as a loanword in Fulfulde in the region, it is of Kanuri origin, meaning “war chief” or “youth leader.”42 While most articles on Nigerian banditry focus on the Fulani, their non-English vocabulary is often exclusively Hausa and Kanuri. They are not making mistakes; rather, they are illustrating the extent to which the social factors which incentivize conflict in the region are not specific to the Fulani as an ethnic group, and would persist even were the Fulani not there.

Kingsley Madueke led a team of researchers who wrote for ACLED in 2025 that bandits, despite lacking a central organizing facility, had lately vastly decreased their acts of violence, driven by a decrease in acts of violence targeting individuals. In other words, they were becoming less terroristic. At the same time, they were becoming no less active, and they continued “coercion of local communities” with their rent-seeking targets including miners, pastoralists, and farmers.43 And while bandit group bureaucracy is not as complex as that of the old Massina empire, it is nonetheless “complex [], adding to their resilience.” Groups, which on the small end may have just thirty members, can have as many as 2000. A kachalla has a deputy underneath him; the deputy oversees “the intelligence and logistics units,” which outrank “foot soldiers.”44 They go on:

At the lowest rung, separate units exist for cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom, motor bike riders and providing security at the camp, along with looking after kidnapped victims. While each of these units specializes in a particular illicit activity, they all participate in the extortion of farmers and miners, the collection of levies from communities and the enforcement of forced labour.45

Their governmental capacity can be quite high. As Schouten and Barnett were told in one interview, “In these villages, they have imposed their own rule. They can do justice, they can decide everything, take what they want. They may not always be there, but if somebody beats his wife, informers [are instructed to] call them and they come. They are rulers.”46

Schouten and Barnett point out that bandits, while fluid in their attachment to territory, do hold territory at varying but discernible levels of control:

Spatial data confirms that power radiates outward from bandit heartlands, where bandit leaders establish stable cores, to tribute zones, where communities are subjected to levies or coerced labour, and further to raiding frontiers, predatory zones where violent appropriation predominates. These layers, mirroring historical patterns, at once reflect the integration of different uses of violence by bandits as well as their spatial dispersal.47

Because a single bandit group may have several “centers” spread between their own natal and other subject villages, abandoned government facilities,48 and places in the bush, what Schouten and Barnett map as a series of concentric circles may in practice be more like a complex, adaptive network of nodes and corridors, intimately tied to the physical and hydrological geography of a place, just as had been the case for settlement patterns in Fuuta Tooro toward the beginning of the last millennium.49 Schouten and Barnett conclude:

[R]ather than representing an intentional spatial strategy, contemporary bandit rule emerges as collateral outcome of adaptation to shifting opportunities and constraints, constituting what might be termed a ‘bandit effect’ in rural governance. This phenomenon represents the unintended formation of political order rather than deliberate state-building.50

Technically speaking, protostates are state-like communities that can do many, but not all of the things that states can do, in which blood kinship is not the main thing holding the communities together. Bandit groups, individually but even more so as collectives, fit this definition to a tee. By logical extension, so too would all major Savannah insurgent groups.51

VI. Bringing the state back in.

Now, the fact that protostates are spreading across the Savannah, the next question might be whether that means that the juridical states where these protostates operate are “failed states.” The answer is: not necessarily. States can undergo civil conflict for extended periods of time without failing. Particularly strong insurgencies can cause state failure, especially under the current international law regime, in which it is hard for a state to legally withdraw from territory which it does not control. But juridical states can survive and even, in certain circumstances, thrive despite facing entrenched insurgencies. Close analysis is the key to understanding what may be the case in any specific circumstance.

As DeAngelo pointed out that JNIM and the Islamic State—Sahel Province, or ISSP, are better understood as insurgencies than as terror groups, a natural conclusion is that they should be fought using counterinsurgency rather than counterterrorism strategies and tactics. He writes that Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger “have relied on repression and decapitation, employing security forces to clear areas and kill and capture terrorists, especially the leaders. They have inconsistently employed persuasion, which can involve negotiations to reduce violence or to demobilize and splinter groups.” The same has largely been true of Nigeria.

DeAngelo writes of the governments facing insurgencies, “their objectives should be [territory and] population-centric, focused on securing localities and improving governance. That their populations perceive jihadist groups as, in some cases, providing better security and governance shows the extent of their shortcomings.”

In theory, this should not be a problem; by the time the French launched Opération Barkhane in Mali in 2014 to replace the previous Opération Serval there, counterinsurgency was at least nominally part of the approach. I say “nominally,” because the French themselves had a fairly limited total footprint, and the counterterrorism approach was seductive to them and their state-based allies for a long time. Thus Mathieu Pellerin was able to frame his 2019 report as a call to stop underestimating the extent to which jihadist groups in West Africa were insurgencies.52

Even in 2022, when Opération Barkhane was discontinued, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an American thinktank, was not alone in framing Barkhane as more of a counterterror than a counterinsurgency effort. Many individuals in the senior and mid-level military leadership which now participates in the dictatorships of Sahelian countries received training under Barkhane and associated French, American, and European, efforts. Their responses to jihadist violence have, as DeAngelo points out, been more focused on counterterrorism tactics, which are relatively lighter-touch and can provide quick wins, than on counterinsurgency ones.

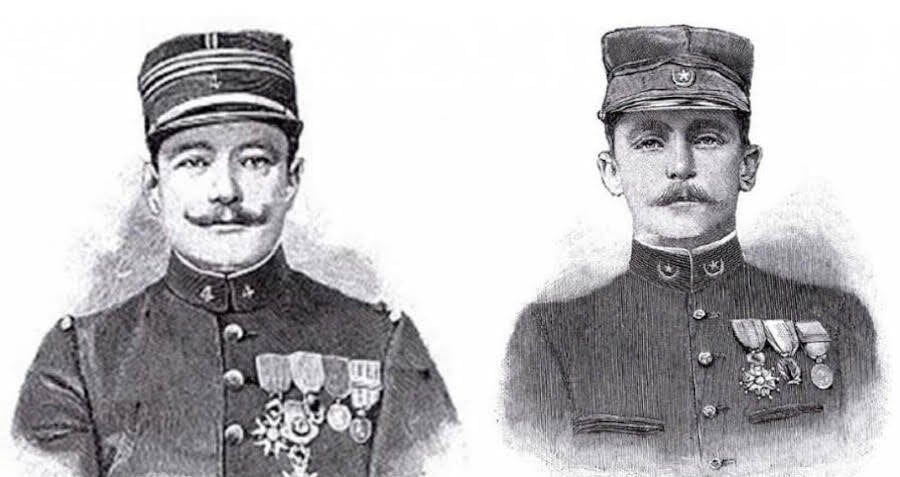

The problem is not limited to those three countries. In her history of the French colonial conquest of Burkina Faso, Jeanne-Marie Kambou-Ferrand writes,

If Dori’s role as a commercial crossroads was acknowledged by a unanimity of observers, there were many who, according to [French officer Georges] Destenave, underestimated its political influence, which was “considerable and extended much farther than the small extent of its territory might suggest. . . Dori is the key to the north and the east of the Niger River’s bend,” he recalled. “According to tradition, he who is the master of Dori, controls the Tuareg and all the lands down to Say,53 and could control the Niger’s Hausa bank down to the gates of Sokoto.”54

Destenave may have been underestimating Dori’s importance, since he was coming from the west, and so to his purposes the reaches of the Niger above Dori were already pacified; from twenty-first-century perspective, that city’s strategic value extends in all directions, especially far when running parallel to the axes of the river. This is a lesson that Destenave’s twenty-first-century successors, African, American, and European, seem to have ignored. While drone and special operations warfare around Dori was often quite pitched, at no point in the twelve years since I first started travelling to Burkina in 2013 has that part of the country been pacified, and the rest of the region has deteriorated accordingly.

Illustrating that the strategic and tactical problem is not merely a francophone one, the retired Nigerian general Fatai Ali argued in a July 2025 blog post for the London School of Economics that Nigeria was relying too heavily on a mix of drone warfare and highly trained special forces who deploy and withdraw on a reactionary basis than on the regular army, whose units look to hold large swaths of territory until they are relieved. It is a sadly common problem. Schouten and Barnett implicitly agree with Ali’s analysis when they write, “Even the Nigerian armed forces rely on raiding tactics, targeting suspected bandit settlements with air strikes that often result in civilian casualties and ground raids marked by material destruction.”55

VII. Disloyal oppositions.

Even the most formal states can engender significant opposition, both along their borders and within their territory. The Massina Empire in what is now Mali and Burkina faced three main opponents. One was the Tuareg, just to the north.

Long an external enemy to Massina, the Tuareg, like the Fulani, had a large nomadic population; perhaps even more so than the Fulani, their society at the time was deployed around the distribution of people and goods forcibly acquired from razzias. In the second generation of the empire, after a lightning military campaign, the Fulani and Tuareg reached a diplomatic agreement that pacified their border and established Timbuktu’s fealty to Hamdallay.56

The Bambara of Segou, on the other hand, had been longer-established as governors of a state in the region than was the Massina Empire headquartered in the new city of Hamdallay.57 Like the Fulani, the Bambara were led by a noble caste which regulated and taxed agriculture, trade, and artisanry. Along a broad, productive swath of what is now central Mali, the two states faced off against one another, competing for the rents of the rest of the area’s population.58

And of course, there were the Toucouleur and their allies who came from Fuuta Toro and established a short-lived empire very similar to the Massina that it overran before being defeated in turn by the French.59

In northwest Nigeria, the Yan Sakai (“volunteer guards” in Hausa) are vigilante groups that simultaneously claim to defend populations against Fulani aggression and, by targeting Fulani groups, incentivize young Fulani men to take up arms.60 Given the acephalous nature of the bandit community in northwest Nigeria, it would no more do to model the Sakai as external to that community than it would be to model Ghana’s New Patriotic Party as external to the Ghanaian state because it is in opposition to its government. Yan Sakai is a party to the protorepublic of banditry. This is true even as, in the words of Abiodun Jamiu, “The state has [] been wavering on how to address the rise of vigilantism, at times outlawing the Yansakai while at others considering rolling the vigilante militia into security forces and mainstreaming them.”

According to an ECOWAS commission report in 2023, in Burkina Faso, Koglweogo, while nominally citizen self-defense groups, were “often established along ethnic lines,” just as such groups tend to be throughout the region. The report goes on:

[T]heir role in resolving conflicts over land issues typically benefitted Mossi communities, the dominant ethnicity within the Koglweogo, at the expense of the Fulani.

Tensions rose even higher when the Koglweogo became involved in counter-insurgency. Under the pretext of defending their communities, they began to launch pre-emptive attacks against neighbouring communities, predominantly Fulani, whom they accused of being aligned with violent extremist groups. This exacerbated tensions between both communities, fuelling tit-for-tat attacks and a series of massacres on both sides since early 2019, which remains the deadliest year for civilians in Burkina Faso. Eventually, this discriminatory exercise of quasi-judicial power resulted in some targeted communities seeking protection from extremist groups in the country.61

Here again, we see citizens’ militias participating economies of violence and expropriation in the name of opposing violence and expropriation. In 2020, as the situation worsened, Burkina Faso’s government tried a radical reform of the Koglweogo: a broad-based nationalization. The commission writes:

In 2020, as more and more of the national territory fell to violent extremist groups, the Burkinabe parliament passed a law that established the [Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland, or] VDP, recruiting civilian volunteers in their villages to help defend the country and absorbing the vast majority of existing self-defence groups. The VDP’s actions, like the Koglweogos, have heightened communal violence. Civilian casualties doubled between 2021 and 2023 (from approximately 750 to 1 500); in 2023, one-third of these casualties have been attributed to armed violence from state forces or its auxiliaries. VDP members have also engaged in criminal behaviours, such as racketeering, kidnap for ransom and cattle rustling.62

When rent-seeking insurgency is an activity which gives impoverished and underemployed rural youth activities, meaning, and unprecedented financial throughput (though not by any means wealth), if the state does not have the resources to buy such youth off by enlisting them into the army and making them sleep in barracks, march on parade, and perform details, then asking community members to approach the practice of insurgency, that is the eternal risk. The imagined self-defense squads risk become rent-seeking robber bands and warlord-led militias with haste and unity of effort.

Even beyond their own development, such groups risk catalyzing the insurgencies they set out to neutralize. Buhari Tsoho,63 also known as Buharin Daji,64 was reportedly a Fulani man who had initially had grievances about ani-Fulani violence in Zamfara State, Nigeria, where he lived. He was described as a “president” or “general” with “governors” serving him.

Tsoho was not unique. Obi Anyakide writes:

The Yan Sakai, formed to protect Hausa villages, began indiscriminately targeting nearby Fulani communities in revenge, forcing survivors to shelter in the forests that ring Zamfara or to flee the state entirely.

The Fulani response was a militia of their own, known as Yan Bindinga.65 Its reprisal raids were seen by some in the Fulani community as a legitimate answer to both vigilante violence and the state government’s deliberate prioritisation of farmer interests. Over time, the Yan Bindinga became almost indistinguishable from the original forest-based bandits.

VIII. Becoming more or less stately.

It is not at all uncommon to see insurgent groups, and even state-affiliated militias, becoming ever more like independent protostates as time goes on.

In late August 2025, JNIM took control of the central Malian town of Farabougou, which had been one of the high water marks of its territorial control in the country before being retaken in late 2020 by what was then Mali’s new military dictatorship. Up to 2025 it was the site of a military base, which JNIM seized in August ten days before taking the town.

To understand the economic and logistical value of Farabougou, a “strategic location” in the words of Le Monde and Agence France Presse, it is useful to understand a little of Mali’s road system. As a landlocked country, much of its imports travel overland from neighboring countries. Imports coming from the port at Dakar enter Mali west of the city of Kayes. Those headed for Bamako or the heavily populated southwest take a southerly route through the country. Those headed for northern, eastern, or central Mali, as well as those that are just transiting on their way to Burkina Faso take a northerly route. Farabougou sits along this northerly route. It is small and remote enough that it is easy for a relatively small force to hold. By controlling Farabougou, JNIM can rent or close the highway at its discretion.

Sometimes, however, insurgencies can become less state-like. Were this to lead to their disappearance, that might be a good thing. If it simply leads to a diminishing level of command and control, and a flair-up of violence as successor statelets vie for supremacy, the results can be a worsening situation for the local population.

In 2024, Kingsley Madueke, Lucia Bird Ruiz-Bentez de Lugo, and Lawan Danjuma Adamu wrote for the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime that the success the Nigerian military had in killing a bandit leader in the northwest “may be a win for the state by ending his reign of terror, but it could also trigger an upsurge in violence and instability as rival factions scramble to vie for control over the lucrative revenue streams generated by the wealthy [leader] and his band, leading to heightened risk of attacks on communities.”

IX. Rendering resistance futile.

I started off on this after reading the two recent fascinating articles by Schouten and Barnett. Their insights set me off on a light round of desk research, and got me to thinking about some of the things I’d read about conflict zones in the Sudanian Savannah over the last several years.

I would love it if all of this led to a great “aha” moment about the future. The only such moment I had was about the present: the realization that the banditry in northwest Nigeria about which I had been reading, mainly in the news, was intimately related to the more formal insurgencies around the region, and that they might all be classified as proto-state communities.

With a bipartisan American congressional delegation having spent four hours in meetings in Ouagadougou in late August 2025, it is possible that relations between the United States and regional dictatorships warms for the first time in years, especially if the dictatorships are willing to hold elections that are at least as free as those of Togo.66

If the Americans do come back into the conflict in Mali, Burkina, and Niger, that might at least give the governments of those countries a broader window of possible options.

Starting at the turn of the early twentieth century, the interior Sudanian Savannah belt saw an Islamist pacifist wave that tied itself intellectually to the insurgent jihads which had come before without in the least condoning their methods.67 It was not an outcome that many might have foreseen in the 1890s, though it may have been in line with some of the very last teachings of Usman Dan Fodio of Sokoto and Shayku Ahmadou of Massina.

Whatever happens today, it would be nice if affected communities were able to settle into their homes, provide as confidently as the world allows for their families, and enjoy for themselves a measure of rest.

For the sake of concision and to avoid confusion with the sovereign state, henceforth “the Savannah.”

(Kane 1986/2004, pp. 49-53, fig. 9)

(Mazrui 1986, pp. 73f)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025b, p. 7)

(Kane 1986/2004, pp. 59-67, 69-72, 74-76)

(Kane 1986/2004, pp. 67-69, 74-76) On this same question, I look forward to reading Cheikhna Wagué’s Histoire des Soninkés dans le Fouta Toro (2025). It is my understanding that Wagué focuses exclusively on people descended from what Kane refers to as the post-1790 wave of Soninke settlement, who do not incorporate Fuutaŋke identification into their quotidian cultural practice.

(Kane 1986/2004, pp. 67, 83)

pël

(Robinson 1914, p. 98)

These languages, which influence one another, are from extremely different branches of the global linguistic tree: Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan.

In general, questions of terminology and identity are significantly complicated that the overlapping groups of Fulani people and experts on the Fulani can and do regularly score easy “points” for themselves by noting how others’ categories don’t quite work.

(Bazémo 2007, p. 248)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, pp. 13, 65)

(Bâ 1991/1992, p. 22). For Fuuta Jula (Kane 1986/2004, p. 26)

(Pellerin 2019, p. 23f and footnote)

(Pellerin 2019, p. 27)

(Akinwumi 2001, p. 335)

(Akinwumi 2001, p. 335)

(Akinwumi 2001, p. 343)

See also Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 11

(Akinwumi 2001, p. 339)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 23)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025b, p. 20)

(Dieng pp. 259-260, 264-266, 270)

(Diallo 2023, p. 22)

(Diallo 2023, p. 75)

(Bâ 1993/1994, p. 13)

(Bazémo 2007, pp. 53f)

(Coquery-Vidrovitch 1993, p. 138)

(Lovejoy 1990, p. 159)

(Diop 1987/2012, pp. 48-71, 118-120, 169-173, 187-204)

(Courtright 2025, p. 3)

(Bâ and Daget 1955/1984, pp. 61-76)

(Bâ and Daget 1955/1984, pp. 81-83)

(Pellerin 2019, pp. 26f)

Often framed as armed community self-defense groups, a lengthy and anodyne turn of phrase. When groups of people who identify with a localized community informally use lethal and expropriatory force against others whom they understand to be transgressive, the groups in question are mobs, posses, or militias.

The word variously spelled ruga, rugga, rouga, and rougga is highly contested. When in 2019 Nigeria developed a system of RUral Grazing Areas in eleven or thirteen mainly northern states under the presidency of Muhammadu Buhari, it was suggested that the name was chosen in part to create an acronym that matched the Fulani word for “settlement.” In 2021, a group calling itself the National Union of the Rugga of Burkina, or UNRB, was reported to say that rugga meant “chief of shepherds.” An early Hausa-English dictionary defined ruga as a noun meaning “a Fulani cattle camp,” or as a verb “not in general use amongst the Hausas” meaning “to make flee” or “to flee” (Robinson 1913, pp. 2, 300). An early Fulfude dictionary focusing on the dialect spoken in Adamawa, Nigeria, gave rūga as “go in a body” and rugga as “rout, disperse, drive back in disorder” (Taylor 1932, pp. 160). A late multi-dialect Fulfulde dictionary from the Summer Institute of Linguistics defines ruggaade as “to clear the ground” and features no closer match to ruga (Smith 2016 p. 569). “Ruga” as a social or geographic reference may have entered both Fulfulde and Hausa in the central Savannah.

(Pellerin 2019, p. 25)

(Pellerin 2019, p. 41)

(Jarrett 2007, p. 63)

(Madueke et al. 2025, pp. 13, 19)

Likely a misnomer, given bandits’ frequent utilization of motorbikes for transport. Bandit groups can be thought of as autonomous mechanized cavalry units ranging in scale from a platoon or troop to a battalion.

(Madueke et al. 2025, p. 19)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 35)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 28)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 38)

(Kane 1986/2004, pp. 44-49)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 63)

In proposing this conclusion, I separate myself somewhat from that of Schouten of Barnett. While relying heavily on their analysis, I do not join the conclusion that northwest Nigerian banditry is fundamentally more adaptive or less strategic than are jihadi groups in the region to such an extent as to require them to be considered as distinct phenomena.

(Pellerin 2019, p. 11)

a city in Niger southeast of Niamey

(Kambou-Ferrand 1993, p. 199)

(Schouten and Barnett 2025a, p. 55)

(Bâ and Daget 1955/1984, pp. 260-266, 273-285)

(Bâ, Kesteloot, and Samburu in Kesteloot and Dieng 2009, pp. 332f)

(Bâ and Daget 1955/1984, pp. 266-268)

(Bâ and Daget 1955/1984, p. 233)

(Hassan and Barnett 2022, p. 10)

(Le Cour Grandmaison et al. 2023, p. 11)

(Le Cour Grandmaison et al. 2023, p. 4)

Tsoho is a Hausa surname also found among the Fulani of Nigeria and Niger.

“Buharin Daji” is said to mean “Buhari of the bush”; daji means bush in Hausa (Robinson 1913, p. 59); it is an uncommon enclitic in Kanuri referring to edge cases (Jarrett 2007, pp. 23, 29).

Bindinga is Hausa for “rifle” (Robinson 1913, p. 38); بندقية is the Arabic.

As written up in the Africa Report (paywalled English, and French via Jeune Afrique)

(Bâ 1980/2014, pp. 158f)

An excellent index of the crises and dynamics of this moment! Ever so complex, ever so necessary to examine.