Not long after I started reading Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux’ Philosophies africaines, the sad news came that the Congolese philosopher V. Y. Mudimbe had passed away.

Before going further, it is worth noting here: Somehow, without much noise being made about it, we have found ourselves in the middle of a golden age of African philosophy. While political scientists, historians, economists, sociologists, and legal scholars may be more well-known than their colleagues in philosophy departments, these latter have been addressing themselves to the important and challenging question of how Africans and Afro-descendent people think in this age after legal colonization, being informed by past and present experiences of exploitation without being defined by them.

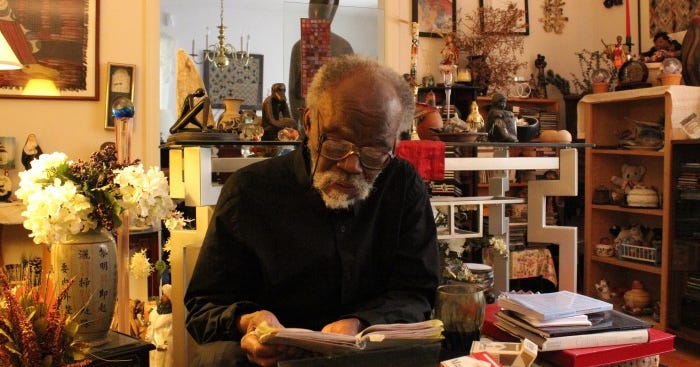

Mudimbe was responsible for putting clear terms to an important early step in the contemporary development of African philosophies. His writing was every bit as relaxedly, playfully, and confidently trenchant as you might expect from the bemused and enigmatic expression he often wore in photographs.

Born Valentin-Yves Mudimbe in 1941 in the region of Katanga in the Belgian Congo, he studied briefly in Rwanda shortly after independence and then went to university in Belgium, returning with a doctorate in the 1970s. In his absence, Mobutu had rechristened the Democratic Republic of Congo as Zaïre, inaugurating the era of “authenticity.” In accordance with government directives around naming conventions, Mudimbe went by Vumbi-Yoka for several years; overall, he is best known by his two leading initials. During this time, Mudimbe became a university professor in Kinshasa, with his most enduring work product from this period being several novels.

Zaïre, Katanga, Shaba, and the departure.

Meanwhile, the region of Katanga had become politically essential to the country’s administration, international legitimacy, and stability, a status it retains to this day. Even before Mudimbe had gone to university, the Belgians, while formally granting independence to the Congo, wished to retain access to Katanga’s mineral wealth while being significantly less interested in the rest of the country. So, in 1960 they encouraged regional leaders to secede from Congo. The next year, a young Mobutu overthrew the civilian politicians who had rapidly promoted him through the armed forces, including prime minister Patrice Lumumba, whom he released to the rebels in Katanga. The rebels killed Lumumba and Mobutu cemented his ties with the United States, a Belgian ally.

Within months of his second coup in 1965, in which he swept away the last vestiges of democratic rule in the country, Mobutu crushed the initial Katanga revolution. Mobutu and his western backers thus ensured that no Congolese election would bring to power politicians who might consider selling the region’s industrially strategic minerals to the Soviet Union. The surviving leadership of the free Katangan state fled to Angola, where a Soviet-supported rebellion against Portugal maintained a stronghold along the Congolese border.

When the authenticity era was launched in 1971, Katanga was renamed Shaba in reference to copper, one of its principal products. Angola won its independence from Portugal in 1974, and three years later, Katangan veterans of that war returned to Shaba as part of the Congolese National Liberation Front, kicking off what would end up being two wars in two years against Mobutu’s Zaïre, now supported by Belgium, the United States, and Egypt and Morocco, the latter two being African countries which were in the last stages of intricate and contingent diplomatic maneuvers which saw them transition from the heart of the non-aligned movement to the core of the American sphere of influence in the Global South.

Not long after the final defeat of the Shaba rebellion in 1978, Mobutu, whose taste for political intrigue had not dimmed since the days he overthrew Lumumba, invited Mudimbe, the professor from Katanga, to a senior role in the Zaïrean government. Mudimbe instead opted for exile in the United States, where he would hold a series of professorships.[1]

Reflections from exile.

Within Zaïre, Mudimbe had kept up a constant stream of article-length publications, but it was his extended sojourn in the United States, which was to last until his death in mid-2025, that saw him transition from a writer mainly of academic articles and novels to a writer of book-length discourses on colonialism in Africa. This second stage of his career would see him illustrating a point Edward Saïd would make in his 1984 essay “Reflections on Exile”: When a thinker has the misfortune of being displaced from his homeland, a minor but intellectually productive consolation of the deracination is a critical distance that can enable some of his best work. So it was for Mudimbe.

The first full-length study he produced in America, L’odeur du père, saw him approaching two developing streams of academic concerns. Published in 1982, it was a discursive, essayistic work, exploring how knowledge production in the Global South was often dependent on discourses in the Global North. Six years later, in his English-language masterwork, The Invention of Africa, Mudimbe would write,

First, the capitalist world system is such that parts of the system always develop at the expense of other parts, either by trade or by the transfer of surpluses. Second, the underdevelopment of dependencies is not only an absence of development, but also an organizational structure created under colonialism by bringing non-Western territory into the capitalist world. Third, despite their economic potential, dependencies lack the structural capacity for autonomy and sustained growth, since their economic fate is largely determined by the developed countries.

In support of this conclusion, he would explicitly cite leading anglophone and francophone dependency theorists: Samir Amin; André Gunder Frank; Walter Rodney; and Immanuel Wallerstein.

More core to philosophic discourses was Mudimbe’s reflection on the scientific method in the social sciences. He would expand on this in time, both in the depth of his engagement and in his citation of his clearest antecedent: the Beninese philosopher Paulin Hountondji, who passed away a little over a year before Mudimbe. Mudimbe’s own philosophic legacy would lie chiefly in taking Hountondji’s core academic project and using it to understand how Europe produced and domesticated knowledge beyond its shores.

Critiques of ethnophilosophy.

So who was Paulin Hountondji, and what was his grand project?

To begin with, a headnote: While it is a useful shortcut to talk about countries and thinkers by language set, one of the first things that comes out of a comparison of francophone and anglophone philosophy and literature in Africa is that, even as their references are distinct and often shaped by their language, there is nothing inherently anglophone about certain African ideas; nothing inherently lusophone or francophone. Thus, while francophone writers of fiction from Boris Diop to Amadou Hampâté Bâ continued to engage actively with folklore in their works even as their anglophone peers who gathered at the African Writers’ Conference disdained it, among philosophers, the split ran in the opposite direction. Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux, the author of Philosophie africaines and an authority quoted in the New York Times’ obituary of Mudimbe, talks about how in philosophy, the divide ran the opposite way. Anglophone philosophers in the 1970s and 1980s set about theorizing a fertile continuum of systematic thought with, on one end, popular cosmologies and folk knowledge, and on the other, more or less systematic philosophy. The Ghanaian Kwasi Wiredu and the Kenyan Henry Odera Oruka set the groundwork and the earliest outworks of this movement.

Among francophone philosophers, on the other hand, clearly rejecting the outputs of what Hountondji, from 1969, called “ethnophilosophy,” was an essential project. It is clear why: The Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne later recalled that in the colonial period, there were no philosophy departments in francophone Africa, but only anthropology departments from which philosophically inclined researchers might work if they grounded their efforts in attribution to specific ethnicities of interest to colonial administrations.

Mudimbe’s philosophic legacy would lie chiefly in taking Hountondji’s core academic project and using it to understand how Europe produced and domesticated knowledge beyond its shores.

European ethnographic production in Africa was fevered. In the early years of the scramble for Africa, Adolphe Burdo and Charles de Martrin-Donos published the multi-volume work Les Belges dans l’Afrique Centrale: Voyages, aventures et découvertes d’après les documents et journaux d’explorateurs. English-language knowledge production was not far behind; the International African Institute published the fifty-volume Ethnographic Survey of Africa between 1944 and 1978. It is still in print, and don’t let that link scare you—it can apparently be yours straight from the publisher for the relatively lower eye-watering price of £1,275.

Hountondji, who studied with Louis Althusser in France, shared his mentor’s particularly Marxist combination of a valorization of scientific exactitude and a dismissal of positivist methodologies—a nearly perfect skill set for the task he was to take on. His ideological legacy insisted that a social discipline, to be a science, needed to have a totalizing theory that accounted for the reproduction of the system under study, which informed the techniques or processes used by practitioners of the science. At the same time, its explanatory engine must both account for the fact that repression and exploitation exist and not be merely mechanistic in how it accounts for social events. The Althusser/Hountondji bar was very high, and Hountondji did not initially interpret either African cosmologies in and of themselves or the voluminous work of ethnographers as clearing it (back in Europe, Althusser wielded his standard in face of his peers’ and predecessors’ efforts with similar results, and published a vanishingly small proportion of his own writings, perhaps himself unable to meet his own exacting standards).

Critique of negritude.

Hountondji and affiliated francophone African philosophers also dismissed Negritude, if not in the form it was elaborated by the Martinican Aimé Césaire, then certainly in the shape it took under the hands of Césaire’s collaborator Léopold Sédar Senghor, a poet who, like Césaire, went on to serve in the French National Assembly. Césaire was initially a member of the French Communist Party, changing affiliations in 1956. Senghor, like Césaire, first took office in the wake of the Second World War. Over time, he shifted his affiliation from the non-Marxist socialists to the Senegalese Democratic Bloc, which was among the first major African parties to break with the Communist Party. By the end of 1960, he was president of an independent Senegal, as erstwhile allies led Côte d’Ivoire and Mali according to independent strategies with which he coordinated only in the loosest terms.

In his role as a co-founder of the Negritude movement, Senghor was heavily influenced by Claude McKay and Langston Hughes, American poets of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote demotic, generalizing verse that celebrated a simple, essentialized blackness. Where McKay and Hughes drew on the blues and jazz for their verse forms, Senghor drew on Sahelian musical traditions of praise-singing. And through Senghor’s verse offers a welcoming invitation to appreciate African art and thought to anyone who might be conditioned, for instance by decades of colonial domination, to undervalue it, it can read as inert, nonspecific, and unreflexive to anyone who has already begun to explore the wealth of African discourses. Mudimbe would offer an unfair but characteristically trenchant dismissal of Senghorian Negritude in his book The Invention of Africa as a simple product of the Bible and French intellectual and literary currents.

A general-purpose critique.

Indeed, the strength of The Invention of Africa was that it was able to put in almost brutally plain terms the Althusserian objections Hountondji and his peers raised to the European reduction of African thought to a living embodiment of a supposedly primitively collectivist stage of human social development. Mudimbe was an acolyte of Michel Foucault, whose hegemonic studies provided detailed understandings of the byways of power without much accounting for the ways in which the oppressed could eventually find their way out of subjection. In line with the Foucauldian approach, Mudimbe focused on the production function of European knowledge of Africa. Thus, he wrote cuttingly about anthropology,

[T]he basic concern of anthropology is not so much the description of “primitive” achievements and societies, as the question of its own motives, and the history of the epistemological field that makes it possible, and in which it has flourished as retrospectivist or perspectivist philosophical discourse [. . .]. Thus ethnocentrism is both its virtue and its weakness. It is not, as some scholars thought, an unfortunate mishap, nor a stupid accident, but one of the major signs of the possibility of anthropology.

Mudimbe’s technique, freed from tightly constrained claims about science and ideology, was sufficiently supple that it could be used to find fault with, or defend, almost any academic enterprise relating to Africa. Thus, he defended the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule’s oft-attacked claim in Dieu d’eau that the Dogon of Mali had an astronomically accurate understanding of the smaller star in the Sirius binary system, invisible to the naked eye,[2] while also dismissing Griaule’s most famous student, the Senegalese historian Cheikh Anta Diop, for conceptualizing several millennia of African history in either negative relation or subordinate dependence to the Eurocentric values animating much African and world history written by white academics. At times in his discussion of Diop, it could feel like you could produce a well-balanced appreciation and critique of Mudimbe’s own intellectual project simply by substituting his name for that of the Senegalese historian.

And so while anyone can deploy the anti-hegemonic technique of cultural criticism demonstrated in The Invention of Africa, the book’s argumentation does not make a particularly stable foundation on which to build anything other than a launching pad for critiques (though in one of his books the Cameroonian political scientist Achille Mbembe has gone further than most from a Mudimbean starting point). Mudimbe’s own subsequent publication history ended up illustrating the extent to which it could be seen as a bit of a cul de sac for anyone looking to see an uncolonized formal system of reflection and meaning-making arise among Africans. Yet “cul-de-sac” is an overharsh analogy, for Mudimbe’s work was also a highly accessible door onto the more extensible work of peers like Paulin Hountondji.

Mudimbe was responsible for putting clear terms to an important early step in the contemporary development of African philosophies.

While a part of the mournful tone of Mudimbe’s obituary is a normal result of reflecting on the passing of a unique and influential talent, another part is due to the fact that the promise of his first decade of work in the United States contributed in only a limited way to the greater philosophical projects in process—he built the door from Eurocentric studies, and then spent further decades perfecting it. The article quotes the Cameroonian philosopher Jean-Godefroy Bidima as writing in La philosophie négro-africaine that “Mudimbe’s project is a circle; he criticized the Western discourse on Africa, even while making use of this discourse.”

Senegalese historian Mamadou Diouf, who today teaches, like Diagne, at Colombia, told the Times, “[Mudimbe] said that the tragedy of African thinkers was not to be able to get out of the colonial library. He was looking for ways to think about Africa outside of the colonial library. He didn’t take into enough account other libraries.”

Leaving freedom in his wake.

Yet those three words from The Invention of Africa, so easy to take for granted once they have been put together, “the colonial library,” served as a great scythe that could clear anything they labeled from the path of countless African and diaspora thinkers. The words were no one’s but Mudimbe’s, and they were perhaps more welcoming to the uninitiated than the more formally exact and actionable ones employed by Hountondji and other earlier pathbreakers. They implicitly established that the work of producing and validating intellectual and cultural work about Africa would henceforth be fundamentally an African and not a European project. Mudimbe demonstrated for all to see that African philosophers would be free to accept or reject any and all European contributions at will.

[1] Attentive watchers of Congolese politics will note that Katanga has retained to this day its central role in DRC political life. Since 2022, the country has faced an insurgency in the Kivu provinces, in the far east. During this period, much of the mineral wealth of the Kivus is reported to have been smuggled through neighboring countries to eager importers in industrialized countries. While this war has increasingly troubled the political center in Kinshasa, it provoked no sudden crisis. But when former Congolese president Laurent Kabila, whose political base is in Katanga, claimed to have returned to the DRC for the first time in several years in early 2025, the government in Kinshasa lost no time in announcing sanctions against him and his political party, and attempting to revoke his immunity from prosecution. The DRC can more or less function as a state for years without economic and political control over its far east; it cannot do so at all if it looses such control over its southernmost provinces.

[2] If Griaule has a positive legacy in the study of Sahelian societies, that legacy is impervious to what we may learn from asking whether he accurately recorded a Dogon hypothesis about the chemical makeup of a star invisible to the naked eye that was both pre-existing and true. His legacy lies instead on his willingness to take seriously pre-colonial African intellectual history, both in his own work, and in his mentorship of subsequent generations of students who themselves became highly influential.