An Africanist perspective on the Roman Catholic papacy

How the Church went from having one African pope per century to having none for fifteen hundred years

I. The African question: 2025

Pope Francis, since 2013 head of the Roman Catholic Church, a faith community with 1.4 billion members of whom one in five are African,1 died on 21 April 2025. As is the case with every pope, discussion of who might succeed him in office started years before his demise and picked up steam immediately thereafter. Francis was an ethnically Italian South American. He was the first pope born outside of Europe in more than a millennium and the first ever Jesuit pope, belonging to a clerical order associated with both the best and the worst of the global expansion of Catholicism.2

There was a sense that both the election and papacy of Francis opened new horizons of possibility for global participation in the Church, and the question naturally arose: Could the next pope be from the continent with the most dynamic, fastest growing population of Catholics? Lists of papabile (literally: pope-able) African cardinals started making the rounds, ranging from some who had held high rank in the Roman Curia, the Church’s senior leadership, to others who, while cardinals in title, had not served in any of the executive posts that for decades and even centuries been proving grounds for the pope-able. And, inevitably, the point was raised: There have already been African and African-diaspora popes—at least three of them. But who were they and what did they do? How can we not be fully certain just how many popes of African descent there have been? And why haven’t there been any at all since the fifth century?3

To answer these questions, it is necessary to take an Africanist perspective on the Catholic Church, while also excavating certain assumptions that have built up over the centuries about what the Church and papacy are. And, honestly, setting up that process was a real headache! This was originally conceptualized as a short, throwaway think-piece, but how do you address readers with contemporary understandings of the relationship between the Church, Africa, and the world at large, bring them back to ancient understandings of those same relationship, and then finish back up with the papal selection?

The way this post will tackle the problem is to move progressively backward through time, pointing out ways in which the Church began to do and profess things that it had not done or professed before, and how it gave up certain things on which it had insisted in the past.

So what are the major periods we’ll be looking at? There are five, each centered around a persistent role popes played within them. In section two, we’ll start with the Ultramontane Papacy, a period that lasted roughly from 1799 to 2013, before leaping back in section three to look at popes as passengers of Western European imperialism, between 1415 and 1789. Section four will look at a long period, from 536 to 1415, when the papacy was captured by different segments of the European nobility. Then, in section five, we’ll see the papacy as the patriarchal capstone of the classical Christian Church, a period that lasted approximately from the sixth decade CE to the year 536. Section six will bring us back to the world since 2013, looking at how the leadership of today’s globalized church relates to Africa, in light of what we’ve found.

Before beginning, a quick note: I didn’t expect it when I started preparing this post, but I came to realize: the Roman Church of Classical antiquity was Roman only in an administrative sense. You can see this administrative lock in the succession of mainly Italian popes, with three Africans and a few others leavened in across the centuries. Yet intellectually, theologically, and spiritually, the Christian Church in its energetic youth was, without exaggeration, a fundamentally and inalienably African community. This post, then, is a story that brings us back to those roots:

II. The Ultramontane papacy: 1799-2013

In 1799, the French and Haitian revolutions were in full swing, rocking the interlocking Atlantic, Catholic, and European spheres. In Jena, an academic center in Germany, a young intellectual going by the name of Novalis circulated a pamphlet called “Christianity or Europe.”4 It is full of normative judgment, and its core theses represented an aggressive revision of even what was known to European historians at the time. Still, those theses, some implicit and some explicit, have since come to be the received understanding that most non-specialist Western Europeans, and the non-specialists they have taught in their languages overseas, have of the relationship between Christianity, Catholicism, Europe, and Western Europe. Namely:

Western Europe fundamentally is Europe; almost no knowledge of history extraneous to Western Europe is necessary for knowledge of European history

Europe is historically a Christian community, and Christianity is historically a European religion

Prior to the Protestant Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church was Christianity

The pope in Rome has always had the relationship to the Roman Catholic Church that the human head has to the human body

The pope has historically had a closer relationship to the Catholic God than have any other people

Perhaps not surprisingly, Novalis would convert from Protestantism to Catholicism after writing the pamphlet. In 1829, Friedrich Schlegel would provide the most clear articulation of Novalis’ arguments in his Philosophy of History. The argument was on its way to becoming canonical in Western Europe.5

In the meantime, on the other side of the Alps, the “Ultramontane” school of Catholic governance was growing ever stronger, and would peak at the end of the twentieth century. While Ultramontanism had meant something slightly different several centuries before, by the time the nineteenth century was over, it came to be centered around the idea of an infallible pope ,the unique vicar of Christ, whose church had immediate spiritual authority over Roman Catholics, who were in turn adherents of the one true Christian faith.

In the Concordat of 1801, Pope Pius VII legally arranged with Napoleonic France for the continuity of the Catholic Church in that country, notwithstanding the fall of the Bourbon monarchy, an absolutist government which for centuries had claimed to rule by divine right and whose kings had been always coronated by Catholic clergy. Republican France would have a say in the promotion of clergy within its territories, just as Bourbon France had done. The Church was simultaneously setting up a hierarchy and diplomatic relations with the United States, though it would take until 1861 for it to establish a diocese in Haiti under roughly the same terms as those extended to France.6 Haiti had declared its independence from France in 1804.

As the century wore on, the Church would set up ever-more dioceses around Africa and the Caribbean, in the process often raising its oldest dioceses in the Global South to metropolitan status. What this meant is that increasingly, “suburban” dioceses like Port-au-Prince, Luanda, and Oran reported in to the Vatican via metropolitans in Santo Domingo, São Tomé, and Algiers rather than through Toulouse or Lisbon. In 1799, Novalis had hoped that the Jesuit order of priests, long associated with colonialism, would be revived, and in 1814, a pope did just that. Many of the earliest effective seminaries in the Global South date to this period, recruiting and training the local population for the priesthood, including Africans and the African diaspora.

With the Church diplomatically engaged with republics and protestant countries, and organized directly in the Global South, it was not rejecting colonialism so much as it was running a parallel colonial enterprise, one that reflected the Church’s longtime rejection of the Westphalian idea that sovereign states could either select in or out of the realm of Catholic activity. In some cases, this meant antagonizing Eastern and Oriental Christians, as when in 1847 it appointed the first Latin Patriarch in Jerusalem since the Crusades, or when in 1951 it established an archdiocese in Addis Ababa.7

As late as 1903, Catholic monarchs in Europe continued to exercise vetoes in the papal selection process. In 1846, an Austrian attempt to exercise its veto was frustrated by slow transport, and a liberal conclave that year elected Pius IX, who, after the European revolts of 1848, would become reactionary and the first major Ultramontane pope of the modern era. While some Italians, living on a peninsula that had long been carved up by continental great powers, had hoped that Pius IX might either lead or support the political unification of Italy, he became as violent an opponent of any form of nationalism as he was of socialism and communism. Pius antagonized the Piedmont monarchy that would eventually become the Kingdom of Italy. That kingdom stripped the papacy of its temporal control of the Papal States, the area immediately around Rome, revoking the right to govern which had been a gift of the Frankish Empire to the Church more than a thousand years before. This did not put an end to the papal traditions of moving around on a litter, a portable throne carried by porters; or of wearing the papal tiara, a solid gold crown much larger than the human head, made in the shape of an inverted beet; or of popes referring to themselves using the royal “we”; or having a complex protocol regarding which of their extremities visitors were supposed to kiss—feet for the less powerful, hands for the more powerful.

It was under Pius that the Church first enunciated the doctrine of Papal Infallibility, and Pius was the first pope to make use of it. In practice, papal infallibility, the idea that a pope, once installed, could be incorrigible on doctrinal matters, is highly constrained: the pope must be sitting on his throne at the time that he speaks doctrinally, be speaking about something that had heretofore been a matter of uncertainty or debate, and he must verbally invoke his infallibility. This has been done very rarely over the last 150 years, but the fact that it could now be done at all naturally antagonized non-Catholic Christians and people who were aware of the deeply political nature of the papacy, which included much of the population of the Italian peninsula. The Kingdom of Italy sacked Rome in 1870, appropriating the city for its own capital, shortly after the First Vatican Council announced that Pius was infallible. The papacy would eventually make peace with Italy, though given trends in both the Church and the country, this would not happen until 1929, when the country had become a fascist dictatorship under Benito Mussolini, eager to associate itself with institutions associated with tradition.

Yet the Church’s direct engagement with its faithful did enable it in some instances to be more humanitarian than the governments of the territories where it operated. The first American priest of African descent was a man who passed for white8 and was ordained, and later consecrated a bishop, in Rome. The first dark-skinned black American priest was also ordained in Italy after failing admittance to American seminaries, which started graduating black priests in 1891, just as the country was otherwise falling into one of its periods of particularly virulent racial repression.

There were other signs of an opening up of the Church in the Ultramontane period; the Congregation of the Inquisition, an office of the Roman Curia that for centuries had been used to crack down on heterodoxy and non-Christians, was reformed and renamed the Holy Office in 1908. After the Second World War, popes stopped appointing people as Latin Patriarch of Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and the West Indies. Each of these titles had long since been given to officeholders in Rome; these patriarchates were formally retired in the early 1960s. Meanwhile, in 1953, Joseph Kiwanuka of Uganda became the first African to be appointed bishop in centuries. Seven years later, he became the first African archbishop. The same year, often called the year of African independence for its political events, Laurean Rugambwa of Tanzania was the first African to be named a cardinal in the Catholic Church.

The liberalizing trends of the Ultramontane period culminated in two events of the mid-twentieth century: the convening of the Second Vatican Council in 1962, and the publication of A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian priest.

At the same time, popes gave up much of their most pompous prerogatives in the 1960s, including the litter, the royal “we,” and the tiaras—though decades later, John Paul II, aided by the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, would later be careful to assert that going crownless had been a choice that future popes would be equally free to reverse. The Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith was the name of a once-again reformed Holy Office, whose inquisitional tendencies had not completely died in 1908. These self-humbling decisions saw the papacy reach levels of popularity among both Catholics and non-Catholics that it had not enjoyed in centuries. The tendency of popes since the 1960s not to use excommunication as a tool for expressing disagreement may have played a role as well.

The desire for universalism and the desire to not instrumentalize expulsion and schism had the perhaps unintended result that within the Church a rift became public that for a long time had not been so. In centuries past, Catholics who disagreed with centralizing trends often left the Church, ignored it, or were expelled. Now dissent remained internal for decades on end. Liberation theology, inspired by Marxist teachings, was frowned on by the central hierarchy, but not exorcized; the same went for Catholics who refused to accept the canons of the Second Vatican Council on conservative grounds.

The Ultramontane period ended in moderation, but not before the accession of two popes whose approach to church governance was every bit as centralizing as Pius IX had been a hundred years before.

In 1978, after more than a century of centralizing reforms, followed by the Second Vatican Council, which opened up the Church on terms acceptable to its overwhelmingly Italian cardinalate, those very Italian cardinals did something they had stopped doing in 1523: they appointed a non-Italian pope. John Paul II, born in Poland, was more open to nationalism than Pius IX had been, but offered no significant critiques of capitalism or liberalism until after the failure of communism in 1991. He named an unprecedented number of non-Italians to the cardinalate, including the Nigerian Francis Arinze in 1985. The papacy retained final say in the naming of Catholic bishops anywhere in the world, which enabled John Paul and his dean of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to largely constrain Liberation Theology, which had gotten support from bishops and archbishops, to the juniormost levels of the Church in Latin America. Yet their 1984 formal codified instructions about the dangers of Liberation Theology9 ended up, perhaps unintentionally, establishing a clear, if limited, path for pro-liberation teaching to advance through the Church without suppression from above.

Throughout the twentieth century, both republics and monarchies gradually relinquished to the Church their previous rights to participate in clerical promotions, a tendency that John Paul II would celebrate during his visits around the world.10

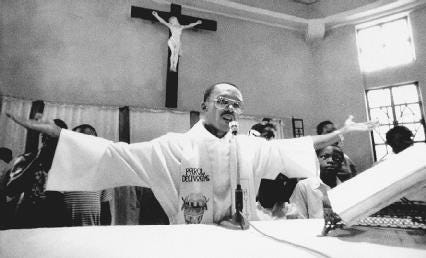

The 1980 assassination of archbishop Oscar Romero, a onetime conservative who developed a sympathy for Liberation Theology, gave a moral weight to the movement for which he died that no number of promoted moderates and reactionaries could counterbalance. The 1990 election of priest and liberation theologist Jean-Bertrand Aristide as president of Haiti may have been the political high-water mark of liberation theology.11 In 1991, the same year Aristide first took office, the Soviet Union crumbled. Three years later, John Paul II convened an African Synod in Rome, confirming that bishops on the continent could and should enjoy the same level of autonomy as bishops elsewhere in the world. In 1999, he published Ecclesia in America,12 which was more generous to Liberation Theology than the 1984 “Instruction” had been; it also critiqued neoliberalism, not from the monarchical position of the nineteenth century Church, but from a standpoint of humanism.

John Paul II died in 2005, leaving behind him a mostly conservative cardinalate with a strong antipathy to schism and excommunication. Cardinal Arinze of Nigeria was among those floated as a potential successor, though his uncompromising doctrinal stances may have counted against him. The same goes for the Colombian Alfonso López Trujillo, who had spearheaded John Paul’s fight against of Liberation Theology in Latin America at the end of the Cold War. An Argentine candidate was the second leading candidate in the conclave that year, but dropped out of consideration, leaving the frontrunner to accede to the papacy: the German who had run John Paul’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith since 1981, and who took the name Benedict XVI.

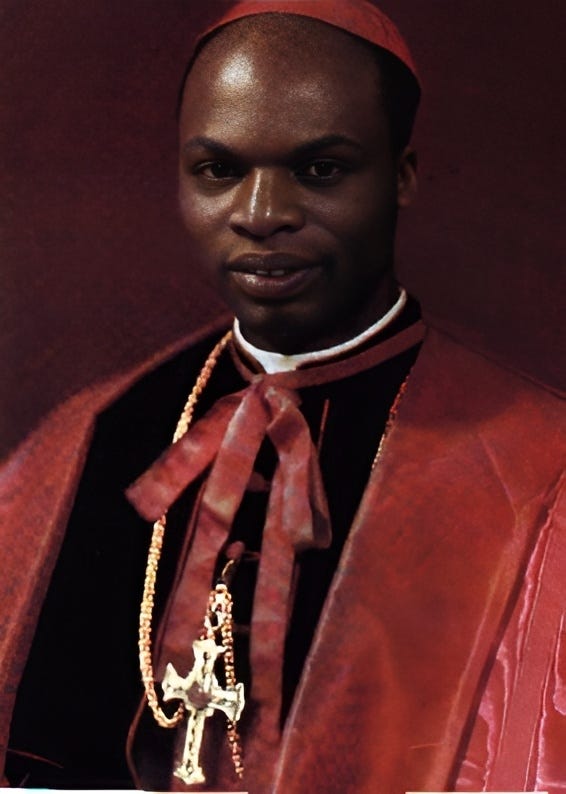

Benedict did not receive the benefit of goodwill that the Church and world had granted John Paul II, with whom he had no substantive disagreements. Instead, all the discomfort with the centralizing trends of the papacy since 1978 manifested itself in opposition to him. Among his personnel decisions with regard to Africa was naming Robert Sarah, of Guinea-Conakry, to the cardinalate. But overall, Benedict’s 2013 resignation marked the end of the Ultramontane epoch. Sarah, every bit as doctrinally hardline as Benedict had been, was among those considered as potential successors, though the cardinals elected for someone who, while personally quite conservative, would better be able to perform the moderating function that the global communion of Catholic faith had increasingly taken on since the Second Vatican Council. This was the Argentine cardinal who had been runner-up to Benedict eight years before. A Jesuit who earlier in his career had fallen afoul of the Jesuit hierarchy for his lack of vigor in pursuit of social justice, he took the eminently moderate papal name of Francis.

Looking back from the start of Francis’ papacy, it seems that the main reason no Africans were appointed pope during the Ultramontane era was that during this period, the church hierarchy, like many Western Europeans, largely accepted the German Romantic idea that Western European society represented the pinnacle of civilization, adding to it the notion that the Catholic Church was the natural spiritual leadership of Europe. Toward the end of the Ultramontane period, the multinational Curial leadership of the non-Italian John Paul II opened up broader horizons, notwithstanding his own Ultramontane impulses.

Pope Francis was the first head of the Church to come from a region formerly colonized by Western Europe. That makes this an excellent time to turn back to the fifteenth century, when Roman Catholic clergy began riding around the world as a part of Western Europe’s global imperial project.

III. The imperialists’ passenger: 1415-1789

In 1414, the Latin Church was in crisis. Crisis was far from new to it, and a formal church council made of bishops, archbishops, and cardinals was called that year to resolve the problem—three popes all serving at once. The council sat for three years. In the meantime, Henrique, a Portuguese prince who would be known to history as Henry the Navigator, participated in his country’s conquest of Ceuta in North Africa, which had previously been controlled by Morocco. Henry would play a crucial role in initiating imperial maritime conquest in Western Europe, but not before the Council of Constance named Martin V pope, replacing all three previous claimants. He immediately established a diocese in Ceuta, with the archdiocese of Lisbon as its metropole.

Martin’s successor Eugene IV, in hopes of decreasing the probability of schisms in his church, named an unprecedented number of “crown cardinals,”: senior members of the church hierarchy who represented the will, and did the bidding, of European monarchs.

In 1453, the Ottomans sacked Constantinople, which had been the seat of the Eastern Christian Church for over a millennium. They continued to host Eastern Orthodox patriarchs in the city, yet the fact that they were now politically subject to a series of non-Christian monarchs meant that the Western Church’s claim to be Catholic, or universal, took on a new shade. At the same time, Christian presence in East Africa was under significant pressure by the expansion of the Muslim faith. Alodia, one of three remaining Orthodox African Christian kingdoms south of Egypt, was sacked in 1474 by an alliance of the Rufa’a and the Funj.13 Increasingly, in a trend that would continue through the later Ultramontane and Globalist periods, the Roman Catholic Church stopped thinking about itself as the Christian Church in the West, and started thinking of itself as The Christian Church.

In the mid-fifteenth century, popes supported Portuguese claims to monopolize the colonization of Africa south of Cape Bojador in Morocco and authorized Franciscan missions to the continent. In 1491, King Nzinga A-Nkwu of Kongo was baptized as João I.14 In Iberia, Isabella I and Ferdinand II conquered Granada in 1492, putting an end to Islamic presence in Western Europe; the same year, Christopher Colombus sailed to the Americas under Isabella and Ferdinand’s patronage, with a Catholic priest aboard as chaplain. The next year, Alexander VI, a Spanish-born pope, published the bull Inter caetera, diving global colonization rights between two European kingdoms: Portugal in the East and Spain in the West. With Rome being the only historical Christian Patriarchy that the Catholic Church still recognized, popes eventually started setting up new, fully Catholic patriarchates. Portugal would be home to the Patriarch of Lisbon, and Spain home to the Patriarch of the West Indies. These were posts higher than archbishop or cardinal, reflecting the extent to which the Church was benefiting from Spanish and Portuguese colonialism.15

Other Western European countries would catch up with Portugal and Spain in terms of power on the continent and overseas. An early indication of the Church’s recognition of this was the 1516 Concordat of Bologna, in which Pope Leo X recognized that the Bourbon monarchy in France would henceforth have a right to participate in clerical promotion in their country. Money was pouring into the Church from the nobility of these expansionist kingdoms; it was used to fund a basilica of superhuman proportions on the site traditionally understood to have been Saint Peter’s grave in Rome.

Leo X would also become the namesake of Al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan, a Moroccan diplomat captured by European pirates and brought to Rome. Under the name Johannes Leo Africanus, Al-Hasan would publish The Cosmography and Geography of Africa, imperfectly recalling his travels and readings in the Maghreb, Sahara, and Sahel. For all the mistakes he made and for all the flattery he offered his captors, his book is a clear reminder of the advantages African merchants and diplomats still had over their European contemporaries in terms of education and worldliness.

Like France, the Netherlands and Britain would also catch up and eventually surpass Portuguese and Spanish colonial conquest, but an event in Germany in 1517 would eventually pull those two countries outside of the realm of Catholic influence: Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenburg, protesting one of the mechanisms by which the Church brought in money, and kicking off the Protestant Reformation. In 1523, Pope Adrian VI, born in the Netherlands, died in Rome. The college of cardinals named Clement VII to be his successor, initiating an uninterrupted 455-year streak of exclusively Italian popes.

Why only Italians? The Reformation drew significant parts of Northern Europe outside of the papacy’s realm of spiritual influence, while also decreasing the ability of the Holy Roman Emperor to insist on his own candidate. Inflows of money from France, Spain, and Portugal made the Church richer than it had ever been, but also balanced one another: The French would not want another Spanish pope granting big concessions to Madrid as Alexander VI had done, and so on. Italian cardinals could present each other as compromise candidates to imperial interests that were jealous of one another.

During this period of an exclusively Italian papacy, the Italian cardinalate benefitted from an unprecedented stability in the Curia, which it used to engage on a several-century long program of reform, much of it reactionary,16 to ensure that the papacy had the temporal strength to withstand attempts by European monarchs to capture it, as they had through the fourteenth century. This was not an effort without reversals: Mutinous soldiers of the army of Hapsburg monarch Charles V sacked Rome in 1527. The fact that Charles’ childhood tutor had been the future Pope Adrian VI may have played no small role in the cardinalate’s decision to keep the Church a fundamentally Italian affair for centuries thereafter.

In the Global South, the Latin Church was active, and this activity would be inseparable from the Atlantic slave trade. Starting in 1516, the priest (and later bishop) Bartolomé de las Casas advocated that Spanish possessions in the Americas stopped enslaving local populations, and use Africans instead. This effort was kicked off in 1524, when Spain transported enslaved Africans captured in West Africa into the Americas.17 Las Casas would be far less influential when he later argued against all forms of enslavement. In 1537, Pope Paul III issued the bull Sublimis Deus, acknowledging that indigenous people have souls and should not be exploited or enslaved. The French, Portuguese, and Spanish would interpret this narrowly as referring only to people indigenous to the Americas; given that slaves were kept in the papal states at this time, this interpretation may have matched the pope’s intent. At various times, the Church as an institution, and several of its clergy, would control some of the largest plantations in the colonies where they resided.

In 1540, Paul III formalized Ignatius of Loyola’s Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits, who would be associated with many of both the proudest and most shameful Catholic engagements with the colonial world. The first Jesuit mission to the Global South would go to Brazil in 1549, three years after Paul III founded the Supreme Sacred congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, best known by the last word of its name. In 1561, a Jesuit would abortively baptize the king of Mutapa, a Shona realm in what is now Zimbabwe.18

As direct Catholic engagement with Africa increased, the Church also downplayed key references to the continent’s early role in its history. In 1586, Cesare Baronio published an update to Roman Martyrology, de-listing, among others, Clement of Alexandria. Catholics also came ever more confidently into conflict with Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christianity on the continent. Around 1621, the Jesuits converted Susenyos I of Ethiopia to Catholicism, in recognition of which Pope Urban VIII named a Jesuit Patriarch of Ethiopia.19 In 1741, exploiting a schism in the Coptic Christian Church, Benedict XIII installed a Coptic-Catholic patriarch in Alexandria.

Flush with support from the Catholic empires of southwest Europe, Pope Innocent X, in 1648, confidently published Zelo domus Dei, declaring the Peace of Westphalia “null, void, invalid, unjust, damnable, reprobate, inane, and completely and eternally without meaning or effect.”20 His declaration would not be influential, but it does illustrate the papacy’s combination of confidence and insulation from protestant Northwest Europe.

In 1659, Alexander VII issued what French historians call “Roman instructions” via the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, carving out French colonial authority from the Portuguese, banning forced conversions, and promoting inculturation and the recruitment of clergy from local populations. Inculturation would lead to reformist tendencies in the Jesuit order, while the promotion of local clergy would start a trend which reached one peak with the elections of John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis as the longest-ever succession of non-Italian Popes over the last fifty years. Clear acknowledgement of French colonial exploitation would ensure both that the Church remained implicated in the Western European colonial project and that it would not fall subject to any one imperial capital.

Meanwhile, the imperialists themselves were getting richer and ever more powerful, and when they acted in concert, they could force Rome’s hand. Thus, over the course of eight years starting in 1759, the Portuguese, French, and Spanish empires each suppressed the Jesuit order. Six years after Spain took action, Pope Clement XIV suppressed the order globally.

The line between being a passenger of imperialism and being subject to emperors was a thin one, and the Roman Catholic Church was concerned about the possibility of falling back into the captivity it had experienced for nearly nine hundred years, until the fifteenth century. But Christianity had never been as strong as it was now in Western Europe, while concurrently, Western Europe’s advantage in political strength over Eastern Europe was greater than it had ever been. In 1791, the German Romantic philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder published Ideas for the Philosophy of the History of Mankind, stressing the historical significance of Christianity in a “Europe” that really was just Western Europe. He also recognized the importance of other religions elsewhere, meaning that he did not go as far as later German Romantics such as Novalis would do. But his world-systems thinking was a harbinger of things to come.

In Catholicism during the early imperialist age, while certain members of the clergy, including several popes, were quite serious about the idea of welcoming non-Europeans not only into the Church but into its clergy, others were not. In any event, no Africans were promoted to bishop during these years. On the whole, the senior ranks of the Church were too consumed with balancing between and benefiting from rising European empires to think about non-European leadership. By the end of this era, even high church offices like the Patriarch of the West Indies or the Latin Patriarch of Alexandria were simply sinecures for Italians in the college of cardinals that could counterbalance the votes of imperial crown cardinals in papal conclaves.

Soon, foundations in Western Europe were shaking as they hadn’t done in centuries. In 1784, after the successful American Revolution, Pius VI established an Apostolic Prefecture in the United States, a former British colony. In 1789, King Louis XVI provoked the French Revolution, while two years later, Boukman Dutty would launch the Haitian Revolution in what was then known as French Saint-Domingue. The possibility of the Church falling captive to members of a dwindling European monarchical order, or even of a total collapse, seemed very real.

IV. The captive bishop: 536-1415

The Latin Church had been here before. In 536, Silverius acceded to the Roman papacy due to the influence of Ostrogoth King Theodahad. Silverius immediately reached out to the Byzantine general Belisarius, who had just conquered North Africa from the short-lived Vandal Kingdom.21 Belisarius entered Rome the same year, deposing Silverius in 537 and installing Vigilius as pope. In 540, Belisarius captured Ravenna, making it the capital of an exarchy of the Byzantine Empire. Seven years later, Vigilius was forced to move from Rome to Ravenna. This was the start of the Latin Church’s “Byzantine Captivity.”

Formally, the Byzantine Captivity would only last until the death of Pope Zachary in 752, one year after the Lombards sacked Ravenna. Yet almost the entirety of the period up to 1415 can be considered a period of papal captivity to one crowned head or another.

Meanwhile, in 553, the Second Council of Constantinople took the unusual step of condemning theologists who were already dead. The theologists in question, Origen and his student Didymus the Blind, were both African, associated with the Patriarchate of Alexandria.22 A centuries-long drip of erasure of prominent Africans from Christian history thus began.

At the same time, the Patriarchate of Alexandria was actually expanding its influence. Theodora was a Byzantine empress whose authority stretched across North Africa after the campaigns of Belisarius. She was passionate about church issues, with a tendency to come into conflict with patriarchs in Constantinople over her desire to advance doctrines that were popular with the laity. Theodora pushed for proto-Coptic Christian missionaries to set out from Alexandria, converting the Kingdom of Nobadia in 543. Alodia converted to Coptic Christianity under Nobadian influence around 580. Makuria would soon follow.

On the other side of the Red Sea, a series of events unfolded that would soon block further Christian expansion in Africa, and eventually roll almost all of it back. In 622, the prophet Mohammed went to Medina, kicking off the Hejira. According to Muslim tradition, in 637, ‘Umar acceded to the Pact of ‘Umar, guaranteeing protected status to Christians and Jews in Muslim lands. In 642, Amr ibn al-As entered Alexandria, completing the Muslim conquest of Egypt. In 709, Musa ibn Nusayr reached the Atlantic, completing the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. While Aksum/Ethiopia, Alodia, and Makuria remained independent east of the upper Nile, no independent Christian kingdoms remained in North Africa.23 As would be the case later, after the fall of Constantinople, leaders of the Christian Church who had succeeded in state capture looked down on their peers who were subject to non-Christian rulers. Of what had once been a Pentarchy, three Christian Patriarchates had fallen under Muslim protection: Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. Only two were subject to Christian monarchs: Constantinople and Rome.

The Lombards, a Frankish people, threatened the Exarchate of Ravenna for a long time, extracting tribute from it starting in 603. In 751, Lombard King Aistulf conquered the Exarchate; when Zachary died the next year, the Lombards installed Stephen II, the first in a series of what came to be known as “Frankish popes.”24 In 756, Pepin the Short transferred sovereignty over the area immediately surrounding Rome to the Latin pope, inaugurating the Papal States over which popes would be monarchs for the next 1114 years; in so doing, Pepin also cemented papal fealty to the Franks.

The Latin Church did try to keep its distance; in 769, Pope Stephen III convoked a Lateran Council, which for the first time in history forbade the participation of laity in papal elections, which were now limited to “cardinal deacons,” assistants of the late pope. This was aan important development, as tradition had long held that the pope was the “bishop of Rome” and that all bishops were chosen by the clergy and laity of their diocese. Cardinals were a recent invention, being initially a mix of lay and ordained managers reporting to the pope. By limiting the franchise to cardinals, the Church hoped to keep at arm’s length monarchs like Aistulf and Pepin.

The hope did not last long. In 800, Pope Leo III, taking advantage of the fact that a woman sat alone on the throne of the Byzantine Empire for the first time in history, declared that the Roman monarchy was vacant, and named Charlemagne, Pepin’s son, “Holy Roman Emperor.” In 862, Pope Nicholas I restored electoral participation in papal selection to the Roman nobility, seemingly in hopes of providing a counterweight to Frankish emperors. Thus, the end result of the attempt to minimize Frankish monarchical intervention was merely the disenfranchisement of the diocese’s commoners. Nicholas died in 867; he would be the last “Frankish pope.” Having outmaneuvered the Franks, the Church put its leadership transitions squarely in the hands of the minor nobility of the city of Rome and its surroundings:; in this case, the counts of Tusculum.

In 902, Ibrahim II, Aghlabid emir, sacked Tormina, the last Byzantine stronghold in Sicily. Two years later, Sergius III became pope. Sergius was the first in a series of popes known to Christian historians as the Pornocracy due to the corrupt intimacy of their relationship with the house of Tusculum. In 924, Berengar I, the last Frankish emperor, died in Verona, while in 955, the last pornocratic pope, John XII, acceded to the Holy See. John, seemingly to counteract the influence of the Tusculans, crowned Otto III as Holy Roman Emperor, marking the start of a long period when Ottonians, Tusculans and another segment of the Roman nobility, the Crescentii, competed for primacy in papal elections.

Multiple popes reigned simultaneously during several stretches of time. Simultaneously, the relationship between the pope, as Patriarch of Rome, and other Christian Patriarchs came to be much less important to the Latin Church than was its relationship with the Western European nobility. Accordingly, Humbert of Silva Candida, a hotheaded archbishop, was appointed to lead a papal legation to Constantinople. Upon his arrival, he excommunicated the sitting Patriarch of Constantinople, who excommunicated him and his associates in return. It was 1054, and Humbert’s spat would long be considered the start of the Great Schism between the Eastern and Western Church, a schism that, because it was deep and never ended, made it possible for Western Europeans to think that their Europe was the only Europe, and their Christianity the only Christianity. The sack of Constantinople, a Christian city, by the forces of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 only exacerbated tensions between the two.

In the eleventh century, the Roman papacy was consumed by the Investiture Controversy. Pope Nicholas II, in his bull In nomine domini, again banned lay participation in papal selection, once again restricting the vote to cardinals. Sixteen years later, Gregory VII published a bull claiming the right to depose the Holy Roman Emperor; Henry IV, then emperor, withdrew his acknowledgement of Gregory, who excommunicated Henry in return.

In 1099, a Catholic army sacked Jerusalem during the First Crusade, expelling the Orthodox Christian patriarch there and installing a Latin patriarch in his stead. Twenty-two years later, when John Oxeites, Orthodox patriarch of Antioch, refused to convert to Roman Catholicism, a Catholic army chased him from Antioch and replaced him with Bernard of Valence, a member of the Latin Church. The idea of the Western Church as the only true Christian Church was becoming ever more deeply rooted in the Western European psyche.

Popes during this period were more reactive to the behaviors of European nobility than they were proactive. Innocent III was upset when he heard that a Catholic army had sacked Constantinople in 1204, but he named Tommaso Morosini as Latin Patriarch of Constantinople anyway.

In 1274, Pope Gregory X decreed that future papal elections must take place under lock and key, that is, with voting cardinals locked in a conclave. In 1309, French-born Pope Clement V, looking to get the papacy to a stable place away from the influence of both the Holy Roman Emperor and the Roman nobility, moved the Holy See to Avignon. (Incidentally, the next year, he named a Latin Patriarch of Alexandria, continuing the recent trend of papal self-importance). This could be considered as the high point of Gallicanism, the belief that popes shared authority over the Church with kings—popes and their envoys crowned kings and emperors, who in turn selected popes. The opposite was Ultramontanism, which we’ve already met in its later incarnation, but which now meant that popes, while not infallible, were supreme in temporal and spiritual matters. For now, Gallicanism was winning: Avignon would remain the seat of the papacy until 1377, and would later be home to a series of antipopes, that is, unofficial claimants to the papacy, in what came to be known as the Western Schism.

Looking across the full history of the captive era of the papacy, it is evident that African and clearly African-descended candidates had no chance to rise through the ranks at this time, given the persistent and successful efforts of European nobility to install maximally pliant favorites on the throne of Saint Peter. Ideologically speaking, the successive generations of European leaders in the Church were white-washing the accepted version of its history during these years, effacing or minimizing the influence of anyone not associated with Western Europe.

By the end of the papacy’s successive captivities, the diverse demands of an increasingly powerful and fractious European nobility became untenable for the Church. In 1414, John XIII, one of three simultaneous papal claimants, called the Council of Constance. The bishops in attendance were fed up with Ultramontanism, Gallicanism, and the conflict between them. They promulgated a third way in a publication called Haec santa synodus, claiming that church councils have their authority directly from Christ, and can act in appropriate ways without the guidance of either popes or kings. This third way was known as Conciliarism, and while the pope eventually selected by the Council of Constance had a successful reign, the monarchies of southwest Europe were about to get very powerful, upsetting the twenty-four-year equilibrium. In the meantime, in 1415, Henry the Navigator was making his way to Ceuta, in Morocco.

The Council of Constance’s synodal, Conciliarist approach would mostly fall into disuse at the highest levels of the Church until the twenty-first century, but it harkened back to a time when the bishops of Rome were in constant conversation with their peers in other major dioceses of the Church, including, even especially in Africa.

V. The patriarchal capstone: 61-536

In the first decades of the Christian faith, it spread rapidly outward from Judea in what is now Israel and Palestine. A common interpretation of the Book of Acts has it that the first Gentile to convert to Christianity was an African, specifically a eunuch in service to a queen of Meroitic Kush. The title of these queens was Quore Kandake and one who reigned in the first or second century was Shanakdakheto. Acts 8:27 refers, in the King James Version, to Philip preparing to baptize “an eunuch of great authority under Candace, queen of the Ethiopians.”25

Immediately after the story of the unnamed eunuch’s conversion, Acts tells of that of Paul, who would become one of early Christianity’s most influential leaders. Paul and several of Jesus’ other apostles crisscrossed the Roman Empire, planting churches. At the time, the three largest cities of the empire were Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome. The dioceses based in these three cities would come to be known as “apostolic sees,” even though several other dioceses were also founded or led by apostles. Peter was at one time or another associated with each one. First came Antioch, a major crossroads on the Mediterranean coast of what was for centuries considered part of Syria but is now Turkey. Antioch was the first place where the name “Christian” was given to the faith community. Then Peter went to Alexandria in Egypt, which according to tradition was initially founded by Mark the Evangelist under Petrine influence. Mark set up the Catechetical School of Alexandria in the city, which for centuries had been the premier center of learning in the Mediterranean world. At this time, the lingua franca of the Church was Greek; there is no evidence that either Peter or Paul, for instance, ever used Latin as a working language. Then, in the 60s, Peter made it to Rome, whose church community had survived intense persecution from civil authorities for about two decades at that point.26 According to Christian tradition, both Peter and Paul were martyred in Rome, treated by the state, like most church leaders at that time and for centuries to come, as criminals to be reformed or extirpated.27

Thus, the first three apostolic sees, also known as patriarchates, were in the three largest cities of the Roman Empire, overweighted toward its eastern half, which had a higher population and was more economically robust than the west. Records are sparse for the early years in Rome and Antioch, but not for Alexandria, which was the literary capital of the Mediterranean. No one bothered to write down a list of who succeeded whom as patriarch in Rome or Antioch until more than a century after Jesus’ death, but detailed and exact accounts existed from very early in Alexandria’s Christian history.

At first, however, even in Alexandria, the idea that the office of “bishop” was separate from that of “priest” had not yet been developed. Broadly, Paul uses the words as synonyms in his letters to the faithful. A lot of ideas later taken for granted by Christians had not yet been articulated, or were just about to be formed. In almost every case, this intellectual development happened outside Europe: Theophilus of Antioch, who had founded that city’s Catechetical School around 170, first used the word “trinity” to refer to the relationship between God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit, about a decade later. Figuring out how to square Christianity’s developing trinitarianism with its Abrahamic monotheism was one of the main preoccupations of theologists and church administrators in the centuries to come.

In 189, Demetrius I became patriarch of Alexandria, while Clement of Alexandria led its catechetical school. Demetrius advocated for what would soon become the default Christian position: that bishops were different than and senior to priests.

At the same time, Christianity was spreading rapidly westward across Africa’s northern coast, both winning converts and troubling those who did not convert—some of whom had ready access to government posts. In 189, the same year as Demetrius became bishop of Alexandria, Victor I became bishop of Rome. He was born in Africa, in what is now Libya.28 Not much is known about his term beyond the firm stance he took on the Quartodeciman Controversy: the debate as to whether the feast of Easter should be celebrated on Passover or on the following Sunday. Victor leaned heavily toward the latter position, excommunicating churches in Asia Minor that celebrated on Passover.

Four years after Victor became bishop of Rome, Septimius Severus, also from North Africa, became the Roman emperor; a crackdown on Christianity that would come to be known as the “Severian persecution” soon followed. In 203, Perpetua and Felicity, two Carthaginian women, were martyred; the same year, Clement of Alexandria fled into the countryside. Origen, who for many years would be one of the most influential of all Christian theologians, took over for Clement at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. He would lead it for nearly three decades, leaving in 231 in conflict with Demetrius.

The intellectual and cultural vibrancy of Alexandria, and to a lesser extent Antioch, leant itself to the theoretical development of Christian doctrine, but a major side effect was factionalism. As a result, these two patriarchates would often loop in Rome when the same theoretical disputes spread across both of their territories. Rome, not having much of an intellectual stake in anything, would then take a position—as Victor had done during the Quartodeciman Controversy—and the matter would be settled. With the Church liking to root all that it did in history and tradition, this consultation process was said to be a recognition of Rome’s status as the last city where Peter served as bishop. Now, the Roman See was the capstone holding the Church together whenever doctrinal disputes threatened to tear apart Alexandria and Antioch.

The Roman Church would grow more intellectual as the years passed. This was largely due to intellectual developments in the African dioceses associated with it. In 210, Tertullian, an African, was the first major theologian to write in Latin; that year, he was also the first to advocate in Latin for the Egyptian doctrine of the Trinity. Tertullian followed where his reason and faith led him, and seemed to split with the standard positions of the Church in Rome as early as 213, presaging several popular movements in North Africa that would be denounced by Peter’s successors in the imperial capital.

In 232, Heraclas of Alexandria ascended to the Alexandrine patriarchate. He was the first of any of the patriarchs to be called “pope.” Sixty-four years later, Marcellinus would be the first Roman bishop to take the title, which to this day is used by both the patriarchs of Rome and those of Alexandria.29

Before the bishops of Rome started to be called popes, there was the Novatian controversy, which split the Church in North Africa before doing the same in Italy. Its origins were in 250, when a new Roman crackdown on Christianity occurred. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, fled into the countryside with many believers who sought to avoid it. Others stayed behind, signing testimonies renouncing their faith. On his return to Carthage, Cyprian insisted that those who renounced must be re-baptized before being accepted back in the Church. This came to be known as the Rigorist position, and he held to it until a conflict arose in Rome between Pope Cornelius and the believers who deposed him and installed the Rigorist Novatian in his stead. Cyprian sided against his earlier position, with Cornelius. This was a rare early instance of the Roman Church being split on a theological issue; it was resolved by Dionysus of Alexandria, Heraclas’ immediate successor as patriarch. He took the same position as Cyprian had. But Cyprian’s bad luck when it came to baptismal controversies wasn’t through: he argued that believers who had been baptized by heretics needed to be re-baptized. Stephen I, bishop of Rome, formally repudiated Cyprian’s position. Later, Roman soldiers came to Cyprian’s house to arrest him. Perhaps remembering his experience during the Decian persecution, he chose not to flee this time, was arrested, and executed.

Not all non-Christians held positions inimical to the young Church. In 270, Porphyry, an Egyptian philosopher, published the Enneads of his Alexandrian teacher Plotinus. The Enneads were a profoundly idealist iteration of Neoplatonist philosophy, opening up a conceptual path that Augustine of Hippo would later develop in his City of God. Alexandria’s history as a center of learning stretched back over 400 years at this point, dating to when Callimachus and Eratosthenes each separately moved from Cyrene, in what is now Libya, to the Egyptian city. A literary circle sprung up around Callimachus, out of which Eratosthenes founded a library.

In 311, the North African Lactanius completed Institutiones Divinae, which surpassed Tertullian and started to rival the works of the Alexandrian school for its rigor, marking an unprecedented advance for Christian theology written in Latin. That same year, on the other side of the Mediterranean, Miltiades, born in Italy of African descent, became the Roman pope. Miltiades sat on the papal throne in one of the most consequential years of Christian history—313, when the Roman emperor Constantine I legalized Christianity throughout the empire, gifting the Lateran palace to the Roman pope. That same year, a priest named Donatus was elected bishop in Carthage, exploiting the same controversy that had ensnared Cyprian sixty years early: the question of whether Christians who sin must be re-baptized. Miltiades called a synod of Western bishops in the Lateran palace to debate the question, insisting that the synod strictly follow Roman legal procedure. There were not yet any Christian lawyers in North Africa, and the Donatists, for as popular as their position was among believers, were unable to present their case under the synod’s rules of procedure, and lost a summary judgment. In 317, three years after the death of Miltiades, Constantine would rule that the Donatists must return to the Roman church hierarchy any church properties they had occupied. This had little effect, so in 321, Constantine shifted course, declaring that Christian sects should be tolerated, and that the Donatists could retain property in their possession. When Donatus died in exile in Gaul in 355, his belief system had become dominant in North Africa.

Regardless of the will of Constantine, Christianity, rather than become more tolerant of disagreement after its legalization, became less so. 313 was not just the year that the faithful could begin to practice openly; it was also the year that Alexander I became pope of Alexandria, and the year that Arius, a North African, joined the Alexandrian clergy. Within five years, Arius would denounce Alexander’s orthodox conception of the trinity. In 325, Constantine, not having had much success in ruling Christianity by decree, convoked the First Council of Nicaea, to which representatives of the three patriarchs and of bishops throughout the empire came. They rallied to the support of Alexander, denouncing Arian and the strain of Christianity that came to bear his name. Though Alexander would die in 328, his deputy and successor, Athanasius I, would be tireless in his attacks on Arianism, whose relatively simple theology would prove popular in the expanding community of believers notwithstanding the crackdowns from senior leadership.

Even with its increasingly complex theology, orthodox Christianity continued to expand its reach. In the 320s, Ezana, king of Aksum, converted to Christianity under the influence of his slave and tutor Frumentius, whom Athanasius made bishop of Aksum in 328. This would eventually become the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Christianity was also expanding into the deserts of Egypt, where its monastic tradition was born. Paul of Thebes had been the first Christian hermit, in the middle of the third century. Paul inspired Anthony of Egypt, whose renown would be so great that he ended up tutoring other hermits who took up secluded residence near him. Anthony’s disciple Pachomius founded Christianity’s first monastery in 318, in Egypt. After Anthony died in 356, Athanasius would write his biography. By the fourth century, Antioch’s Catechetical School was much less active than it had been in its early years, but Alexandria specifically and Egypt more broadly remained the intellectual core of the Christian Church.

In 330, Constantine built up the small village of Byzantium into the city of Constantinople, decreeing it to be the “New Rome” and making it his eastern capital, closer to the culturally Greek spiritual, intellectual, material, and economic core of the empire, and midway between its two largest grain-producing regions: the Caucasus and Egypt.

Serapion became bishop of Thmius in Egypt in 339. He was one of the earliest theologians to develop a complex approach to the Holy Spirit.30 He also sided with Athanasius in the fight against Arianism. Athanasius published in 367 the finalized list of what would become the canonical books of the New Testament, and died in Alexandria six years later, having guided Christianity through the biggest challenges of its first half-century as a legal religion.

In 382, Damasus I, the first bishop of Rome to take the title of pope, invited to Rome Jerome, a theologist from the Balkans who had studied in Alexandria and written a biography of Paul of Thebes. Jerome participated in a church council that decreed that those churches reporting to Rome would henceforth use Athanasius’ list of New Testament books, a decision that would anachronistically be remembered as the “Gelasian Decree.” Jerome would also undertake the translation of the Old Testament into Latin, marking the beginning of the Western Church’s transition to becoming the Latin Church, increasingly doing all of its work in a different language than that of the other Christian patriarchates. The year before, Damasus I had quietly accepted the outcome of the First Council of Constantinople, which raised the Eastern capital of the empire to a patriarchate along with Jerusalem, expanding the three patriarchates into a Pentarchy. The people of Rome were not as equanimous, and rioted when they heard about the watering-down of their diocese’s authority.

In 395, emperor Theodosius I bequeathed the Roman Empire to his sons, giving Arcadius the east and Honorius the west. The western empire wouldn’t survive a single century; the east would continue for over a millennium. In 401, Honorius bought time by moving the western capital to Ravenna. In 410 Alaric I, king of the Visigoths, sacked the city of Rome.

Rome was under threat like it had never before been in the Christian era, but the Latin Church as a whole was thriving. Once again, Africa was the engine. Donatism as a movement had largely moderated, with Ticonius, a Neoplatonist idealist who built on the works of Origen and Plotinus. Ticonius was less important in and of himself than he was in his influence on Augustine of Hippo, the first Latin theologist able to truly surpassed his peers working in Greek. Around 426, Augustine finished both his four-volume study On Christian Doctrine and his City of God. The second argued that the value of the Church should not be measured by the fate of Rome in the years after Christianity became the state religion. Instead, Christianity was an idealized, timeless construct largely untethered from the world in which we live.

Augustine’s idealist conception of Christianity, combined with the increasingly hierarchical and legalistic nature of the Church—both trends born in Africa—would set the foundations of the Latin Church in the medieval period, enabling it to survive the temporal capture of its institutions by one European noble house after another. It also marked a shift that would not be reversed until the papacy of Francis in the twenty-first century: after Augustine, the senior clergy, often for worse more than for better, acted less like guardians and guides for a flock of believers than like guardians of a spiritual faith remote from the human realm.

Soon the Vandals, a Germanic people who had converted to Arian Christianity, lay siege to Hippo Regius in North Africa. Augustine died in 430, during their siege. Five years later, Gaiseric, leader of the Vandals, signed a peace treaty with Valentinian III, the western emperor, establishing a Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, which would never again fall under political control of the Western Empire.

In 451, Marcian, emperor in the East, called the Council of Chalcedon, which unlike most previous church councils exacerbated divides in the Church rather than resolving them. It soon led to schism in Alexandia, with what would become the Coptic Church and Oriental Orthodox going one way, and the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria going another. Roman pope Leo I rejected the results not on theological grounds, but because he felt that it gave too much power to the patriarchate of Constantinople.

In 476 the mercenary Odoacer staged a coup d’état in the western empire, deposing Romulus Agustus in Ravenna and thereby extinguishing the Western Roman Empire. Seven years later Odoacer chose the next pope, Felix III.

When Felix died in 492, he was succeeded by Gelasius I, the last African pope. Gelasius suppressed the Lupercalia, a pre-Christian Italic feast that had continued to be held in Rome after Christianization. Like most Latin popes of his era, Gelasius also antagonized the Eastern Church; he died in 496.

In 527, Theodora married Justinian I and became empress of the Eastern Empire. Seven years later, the Eastern general Belisarius defeated the forces of Gelimer, king of the Vandals in North Africa. He extinguished their kingdom and brought their territory under Eastern, or Byzantine, control. His next stop was Italy, where he would perpetuate the captivity of Roman popes that had started with Odoacer and Felix III.

Looking back at this first period of the Catholic Church, we see three African popes of the Roman Church, a bare count that hardly scratches the surface of African participation in and leadership of the Christian community. Part of the reason there were not more African popes is that the papacy was slow to become anything more than the leadership of one diocese in the center of a culturally and intellectually underdeveloped peninsula outside of Africa. Ambitious leaders could do just as well to rise to the heads of their own dioceses, while ambitious intellectuals would be taking a step backward if they left the rich scholarly communities of Africa to settle in Western Europe. Instead, Africans led the Church from within Africa, mainly from the patriarchate of Alexandria, most of whose popes were African without being Roman Catholic. Yet even those who stayed west of Egypt, like Tertullian, Cyprian, Donatus, and Augustine, fundamentally extended the conceptual boundaries of the developing Latin Church in a way unmatched by their contemporaries in Italy.

The number “three” of African popes is naturally provisional, in part because of poor record-keeping in the early Roman Church, and in part because of population movements in the classical world. A person born in Sicily or Sardinia might have any mixture of Arabic, Berber, Egyptian, Germanic, Greek, Italic, Norman, Phoenician, Syriac, or Turkic heritage, to speak only of the best-documented population movements. And what is true of Sicily and Sardinia is also true for other parts of Italy. Thus, while for three popes it is possible to make the positive assertion that they were African or of African ancestry, for many others, it can difficult to say that they were not of African descent. Europe has never been as culturally hermetic as Novalis would have us believe.

VI. The globalist: 2013-

The fullest acknowledgement of Europe’s relationship with the world outside its borders would come with the accession of Francis to the papacy in 2013. Doctrinally conservative, Francis was perhaps not as learned as Benedict XVI, his immediate predecessor, who had brought a 20,000-book private library with him into the Vatican in 2005. Francis, like John Paul I before him, favored simple, easily accessible homilies, such as the one he gave at his first Maundy Thursday mass, celebrating the anniversary of Jesus’ Last Supper. He told the assembled clergy, “This is what I am asking you: be shepherds with the smell of sheep.”31 He would re-use the metaphor several times across his papacy, encouraging priests and bishops to be ministers to the faithful, rather than Benedict-style ministers to an idealized, Augustinian faith.

Francis was not an Ultramontane, but rather a Conciliarist. This fact was hammered home when he convoked the Synod on Synodality in 2023, giving it relatively free reign, and signaling in advance that he would let its published findings stand rather than capping them with a papal pronouncement. The most radical suggestions made in early stages did not make it through the universalizing stage of the synod, which may have been Francis’ point. He was himself far from radical, and seemed to believe that it was possible to please the faithful by listening earnestly to them, even while not committing to give them all that they want. Here was the Council of Constance revisited, a gentler Haec santa synodus.

Francis was a true moderate, not in the sense that he personally held positions that were between those of radicals and those of reactionaries, but rather that he led the Church’s effort to moderate between a variety of mutually incompatible efforts being advanced around the world by Catholic clergy and laity. He managed to both disappoint and please in equal measure, while decreasing the odds of a schism that has often seemed just around the corner in Catholicism and many other faith communities since the mid-twentieth century.32

When Francis died, many lists of potential African papabile were circulated. Few had held sequences of high office in the Roman Curia that rivaled the pre-selection qualifications of Benedict XVI, Francis, or Pope Leo XIV, the American cardinal who was ultimately selected to replace Francis. In the future, ambitious papabile from the continent will likely need to match recent popes in terms of pre-papacy experience in the Curia.

Chris Ogunmodede, in an excellent, multi-faceted post on Francis’ legacy in Africa, points out that African cardinals under the leadership of Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, archbishop of Kinshasa, successfully pushed back against Francis when the pope green-lit the possibility of clergy offering blessings to same-sex couples in 2023. Cardinal Ambongo may have represented the majority position in Africa when it comes to same-sex marriages; he seems to represent the private beliefs of Francis, and the public ones of Francis’ predecessors. However, a successful papal candidate from Africa could likely be one whose Franciscan skill at diffusing schism exceeds his Benedictine skill at articulating and enforcing particular doctrines.

For now, we have Leo XIV. Shortly after he was named, his family history was published.33 Like Francis, he was ethnically Italian on his father’s side. On his mother’s side, he seems likely to have African ancestry, with his light-skinned maternal grandfather born in Haiti, registered as black in one US census and white on the next, and having lived in a historically black neighborhood in New Orleans. Needless to say, this does not put Leo in the same category as previous popes Victor I or Gelasius I, or even Italian-born Miltiades. But it does highlight the global nature of the contemporary papacy, as it steers the ship of Catholic faith into an uncertain future.

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/262883/worldwide-catholic-population-hits-14-billion

In this post, I use a variety of names for the same faith community, including “Catholic Church,” “Latin Church,” “Roman Catholic Church,” “Roman Church,” and “Western Church,” depending on context.

I am deliberately following Ali Mazrui’s employment of the term “Africa” to correspond to the entire continent.

The argument is often erroneously attributed to G. W. F. Hegel, who was also based in Jena before moving, with most German Romantic intellectuals, to Heidelberg and then Berlin. Hegel’s 1804 Phenomenology of Spirit provided an explanation for the historical and conceptual process by which the impossible becomes the inevitable in response to the inescapable. The Phenomenology, which revolutionized European political philosophy, is notoriously difficult to read. Many students therefore start with, and never go beyond, the pithy and discursive notes to Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion and Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, which provided a bridge between the received wisdom of the German Romantic community, to which they were delivered, and Hegel’s dense and mind-bending phenomenology. Given how long the Lectures are, yet more know Hegel exclusively from short, widely circulated extracts that summarize the beliefs of German Romantics about topics like Western European exceptionalism.

The diocese was established the year after the concordat between Haiti and the Church was signed.

The formal name of which was “archepapy,” reflecting local usage. See below for earlier Christian history in Ethiopia.

The United States is often said to have the “one drop” rule, such that any person with “one drop of African blood” is understood to be black. In practice, prior to the 1960s, there were some very light skinned people with African ancestry, some even with blond hair and blue eyes, who, depending on social circumstances, might engage with the community either as black or as white. A person who knew themselves to have African ancestry but who moved about as a white person was said to a black person who “passed”; their descendants then simply were white—a fact that would become relevant to the papacy in the twenty-first century.

The exact title was “Instruction on Certain Aspects of the ‘Theology of Liberation’”

See, for instance, the text of his speech in Port-au-Prince in 1983: “je remercie de tout cœur Monsieur le Président de la République, qui vient de faire connaître au grand public la nouvelle selon laquelle il est disposé à renoncer de lui-même au privilège, dont jouit actuellement le Chef de l’état Haïtien en vertu du Concordat du 28 mars 1860, de nommer les archevêques et les évêques.”

For the argument that Aristide’s potential was stifled by the United States and other major powers, see Paul Farmer’s frequently updated The Uses of Haiti, especially the third edition. For the argument that Aristide was most effective in opposition in the 1980s, see Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Haiti: State Against Nation.

Papal bulls and letters are known by their first two or three words in Latin. Only the first word and words relating to God are capitalized. In some instances, the first few words reflect the subsequent content; in many others, they form part of an address to God that is chosen because it was not used to begin a previous papal publication.

The Rufa’a were Arab, and the earliest Funj were from Sub-Saharan Africa. Amara Dunqas would later found a Funj Sultanate and, starting around 1523, would pay tribute to the Oriental Orthodox Ethiopian empire. The Christian kingdom of Makuria, in the same part of East Africa, would largely disappear from the historical record by the end of the sixteenth century.

For more details, see

Strictly observant Christians are under a biblical injunction to tithe, that is, to give 10% of their income to the Church. Many exceed this, in hopes of winning salvation or atoning for sins. For a fictional treatment of the extreme munificence the Portuguese and Spanish showered on the Church in this era, see José Saramago’s Memorial do Convento.

The reforms are known as the Counterreformation, and peaked in the nineteenth century at the First Vatican Council under Pius IX.

Spain had already brought some Africans to the Americas as slaves at this point; these had first been engaged as slaves in Iberia.

For more details, see

Alfonso Mendes, the Jesuit in question, would be expelled with his European and Ethiopian followers by Emperor Fasilädäs, Susenyos’ son, in 1634. For details of this episode, see

The conversion of Africans from one branch of Christianity to another continues to the present day, with evangelical Christian churches now often growing at the expense of Catholic, mainline Protestant, and Orthodox ones.

Innocent X here displays a particularly Italian literary tendency to rhetorically skewer that of which he disapproves, a tendency to which readers of church history must inoculate themselves, as it is full of categorical, no-quarter-given denunciations.

At this point in history, the Western Roman Empire based in Rome itself had fallen, but the Eastern Roman or “Byzantine” Empire, headquartered in Constantinople, the “New Rome,” had more than nine centuries yet to flourish.

Origen had certainly influenced heretical tendencies in Christianity. He had also influenced orthodox tendencies; almost everyone was in his intellectual debt, even though methodologies and findings had advanced significantly since his day.

For details, see

Many seemingly foreign popes of the Medieval period were born in Italy; most were either of ethnicities that at the time were not understood to be Italic, or they were Roman citizens who were partisans of the conquering communities. In other cases, ethnically Italic popes were tagged with the identity of their secular superiors.

For more details on the queens of Meroitic Kush, see

I use 61 as the date for the start of this period, but the exact date of Peter’s arrival is unknown.

According to Christian tradition, Peter’s first eight successors in Rome were all also martyred, though contemporary evidence is scarce regarding many of them. The last pope to have been martyred was Martin I, who died in exile in 655.

In this section, “Egypt” refers to the part of Africa under the direct influence of Alexandria, while “North Africa” refers to the African coast west of Egypt, which at the time was divided into several Roman provinces whose borders shifted over the years.

When it is said today that only three popes have been African, this is in reference only to Roman popes. The majority of Alexandrian popes have been African.

“Holy Spirit” is the Christian phrase that gathers together a variety of terminologically heterogenous references in Hebrew and Christian scriptures. The diversity of these references may have contributed to the relative slowness with which a unified theology of the Holy Spirit developed within Christianity, even though the anchoring of the Holy Spirit within the divine trinity dates back to the writings of Theophilus of Antioch.

https://www.thecatholictelegraph.com/pope-francis-priests-should-be-shepherds-living-with-the-smell-of-the-sheep/13439

Catholic provincialism being what it is, many Catholics attribute the current disputatious state of affairs to the Second Vatican Council. The Second Vatican Council does not, however, have causal effect over parallel trends in Protestantism and Islam, to take just two examples.

forbesafrica.com/current-affairs/2025/05/09/pope-leo-xivs-ancestry-celebrated-congressman-genealogist-tout-possible-creole-black-roots/