The dead are not dead.

At a public colloquy on 5 June 2025, toward the beginning of the eleventh session of Raw Academy, the anthropologist Abdourahmane Seck sat under the solid yet slightly moldering thatchwork canopy in the rear courtyard of the Raw Material Company in Dakar. Behind him rose an imposing compound wall of seemingly untreated concrete, with old slogans, assertions, and provocations spread across its surface in chalk that had faded over months and years; far above his left shoulder, out of human reach, was an enduringly stenciled Idia Mask, painted in an unusual side-eyeing quarter view and a FESTAC black and white. Seck quoted from Birago Diop’s poem “Les morts ne sont pas morts” (fr) included in Diop’s Les contes d’Amadou Koumba:

The dead are not under the earth They are in the tree that rustles, They are in the wood that groans, They are in the water that runs, They are in the water that sleeps, They are in the hut, they are in the crowd, The dead are not dead.

According to my notes, Seck was not speaking specifically in the moment about Swiss-Cameroonian curator and Raw Material Company founding artistic director Koyo Kouoh, but he might as well have been. Kouoh passed away on 10 May 2025, as this year’s Raw Academy was in its last stages of preparation. Those who knew Kouoh (among whom I do not count myself) would know what a challenge that timing must have been; in the obituaries published around the world after her demise was announced, the possible effect on another impending event was given yet higher priority: the sixty-first Venice Biennale, to be held in 2026. The Venice Biennale is the oldest and most prestigious art show of its type in the world. Kouoh was only the second African named as lead curator, and the first African woman. The realization of her absence could provoke levels of grief rarely seen but for beloved parents. So while there will be more about the Biennale toward the end here, first, let’s talk about how Kouoh came to be, in life as in death, such titanic news in this big world.1

How to make a scene.

Marie-Noëlle Koyo Kouoh was born in 1967 in Cameroon, where she lived until moving at the age of thirteen, with her mother, to Switzerland. At the end of her studies, she took up a career in banking that she thankfully, given what she would go on to achieve in the arts, did not find fulfilling.

She took up work in arts and culture journalism, which brought her after an initial stab at curation to Senegal in 1995. Kouoh came for the purpose of interviewing Ousmane Sembène.2 Sembene had, in novels like Le docker noir and Les bouts de bois de Dieu, established the avant-garde of the francophone African novel. Looking to reach a broader African audience, he shifted media. His first feature film, La Noire de. . ., ranks on lists of the best movies ever made, anywhere. And while I do not know if he had always been so or if age and experience soured him, by the 1990s Sembène had a reputation as a difficult interview subject. With Kouoh, he did not disappoint.

Before going on, it is worth noting a few things about foreigners’ experience of the city where Kouoh went in search of Sembène. In a pair of 2007 articles, the Kenyan satirist and travel writer Binyavanga Wainaina, who would take up a residency at Raw Material Company in 2014, suggested that a significant amount of Dakar’s most visible foreign-oriented cultural production comes in the form of kitsch, and that otherwise, it is easy to conclude that the city is “fun [. . .] if you can afford it.”3 As the Malian politician Aoua Keïta experienced between 1951 and 1953, it is quite possible for even an effective and tenacious professional, skilled at social networking, to stay long in Senegal and come away with little to show for it, with a sense of being intentionally but needlessly locked out of any meaningful engagement across a series of unimpeachably polite and welcoming encounters. All of which is to say that there was plenty of reason to expect that Kouoh’s sojourn in Dakar might bear no fruit but frustration.

Such would not be the case. Delightfully early in her wait to get enough material to file her article on Sembène, Kouoh met the iconic multidisciplinary artist Issa Samb, who had co-founded a major art collective in Dakar two decades before. He would be her entrée into countless foyers of the Senegalese art world, and she would be the curator that anchored him in the awareness of global art critics and collectors.4 Eva Barois de Caevel, who would be resident at Raw at the same time as Wainaina, wrote of the stream of young people who, thanks to Kouoh, came to Dakar to meet Samb and learn about art history at Raw.5 Kouoh’s putting down roots in Dakar had been prefigured by the networks she had already started building from Europe, but was in large part made possible by the mutually beneficial relationship she built and maintained over more than twenty years with Samb.6

What follows is a bit of supposition. When Kouoh decided, after that first trip, to settle in Dakar, she was a single mother with a young child. That is, she was in the same position Alice Walker was when she turned her hand from poetry to prose, sitting down to write The Color Purple. This was the same position Terry McMillan was when she wrote Disappearing Acts, her first bestseller. It was the same position Buchi Emecheta was in when she carved out time to write Second-Class Citizen. Two things that are not necessarily easy to be are a single mother and a creative intellectual. The one can easily be an obstacle to the other, but in certain cases, the awareness that the time you spend working is carved out from caring for and rearing a person who unconditionally loves and respects you can lead a person to very high standards of craft. Let’s say an unwillingness to settle for anything of so low a caliber as to be a waste of time.

Kouoh built a reputation in the art world as someone who achieved visions. She worked on the curatorial teams at Documenta in 2007 and 2012, and the Swiss pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2008.7 All the while, she was enriching her experience and networks in Senegal, across Africa and its diaspora, and throughout the art world.

When we see us.

In February 2025, Kouoh sat for an interview with Next Is Africa, during which she was asked about her professional moves since 2018. Her answers indirectly reflect on her 2008 founding of the Raw Material Company in Dakar. To start with, the name: “The raw material is the spirit of the artists—not their works.” And: “I asked myself: ‘What does the environment need today?’ The answer was clear: in-depth work on individual practices, with retrospectives and monographs.” And:

The audience is absolutely central. Everything we do is for the audience, for society. We want to nurture a societal dialogue, to improve what English speakers call visual literacy or artistic literacy. It's about educating, facilitating, inspiring, opening up spaces for understanding and exchange.8

In 2012, after four years of itinerance around Dakar, Raw Material Company found its permanent home, a single-story compound on an unusually short, shady, and still street in the middle-class neighborhood of Fann which, like all neighborhoods of Dakar, is otherwise rapidly sky-scraping. The outside looks like any number of buildings under construction, whose finest days must yet be ahead of them. The interior eternally has the bright, freshly painted and quietly humanly humming air of a beloved and just-renovated community library.

Kouoh saw that, even with all the African and diaspora artists working in the Global South, the major centers of art criticism were still in the Global North. Raw, in Dakar, would work to put this world back onto its proper axis, fostering criticism and history made by people from black geographies. Here, it would be made in the Global South. Recognizing that she couldn’t get the kind of institution she imagined off the ground quickly in a university setting, Kouoh set up the Raw Material Company as an independent initiative. It hosts a series of residents like Wainaina, for several months at a time; residencies are often capped by publication of a monograph on a topic at the heart of the resident’s interest. Barois de Caevel wrote of Raw’s service offer to intellectuals in the arts:

I will thus simply say: a yard[;] a family[;] disciples[;] an unjustified uninterrupted flow of words[;] matter at the foot of a tree and under a porch[;] a collectivity[;] something that comes to life, [coalesces], pierces through on contact with words, impulses, outpouring, swarms. [. . .] One might thus also say, a little radically, that a history of art susceptible to studying the objects, forms, and gestures that Issa Samb produced does not exist, or does not exist yet. What is interesting at RAW—and I could not dream of a better example in speaking to you about these exhibitions—is that we navigate precisely between these different ways of producing art history: the traditional and to come. It is at RAW, thanks to RAW, and with RAW (I could say “Koyo”; the two are interchangeable) that I was able to feel myself as not displaced but existing in other systems, and notably in contact with the works of Issa and sometimes with Issa himself.9

From initiative to institution to iteration.

In an obituary for Kouoh whose headline lauded her as “one of [the global art world’s] most original thought leaders,” the Art Newspaper quoted Kouoh as saying in 2024, “I’m a fixer. I like to take complicated institutions and make them sustainable.” The article goes on to discuss the nuts and bolts of how Kouoh went about making organizations durable. With Raw, which she built from the ground up, the first step was getting it from being an itinerant initiative to being an institution. Part of that institutionalization of the Raw Material Company has the Raw Academy.

The Academy is its own production function: how to keep a critical scene self-refreshing. One “session” of the Academy is held each year, and each session would be guided by the vision of a different director. The 2025 eleventh session is under the leadership of Felwine Sarr, a Duke professor of broad-ranging interest and co-author of the Sarr-Savoy Report, which sprinkled needed propellant on the fire that has long burned for the restitution of African artistic and historical artifacts held in museums in the Global North. Directors have significant say in selecting the faculty of their respective sessions, who tend to be a who’s who in a broad variety of spaces and language groups that touch in differing ways on the central topic. One step beyond the faculty of each session stand its fellows, generally of a younger generation with a little less perspective behind them and proportionally more promise in front of them. Most sessions are exclusively for faculty, staff, and fellows, though a few sessions per week, like the one led by Seck and cited at the top of this post, are open to the public.

Sarr’s topic this year is “A Sense of Place: Displacement; Replacement; Non-placement.” I have gone only to the public sessions, and as a result have but a ten-percent view of the iceberg, but the freedom of individual faculty members is notable. It is also reminiscent of how Kouoh’s vision can be seen in the decades of Raw publications: her voice is often wholly absent, or relegated to a place of no particular honor; more often, she is listed as an editor, and even in that set, not given pride of place. Koyo and Raw find the best thinkers they can, and leave those thinkers free to go where their reflection leads them. When I show up early, I hear bubbling through doorways eager conversations, questions, and the embrace of subdued but warm applause. By the time the public session starts, a standing-room-only crowd has gathered and politely hushed. Later, when I rush out the door to get back to my family, I leave behind a half-dozen sibilant klatches of conversation.

But that is 2025: I am getting ahead of myself.

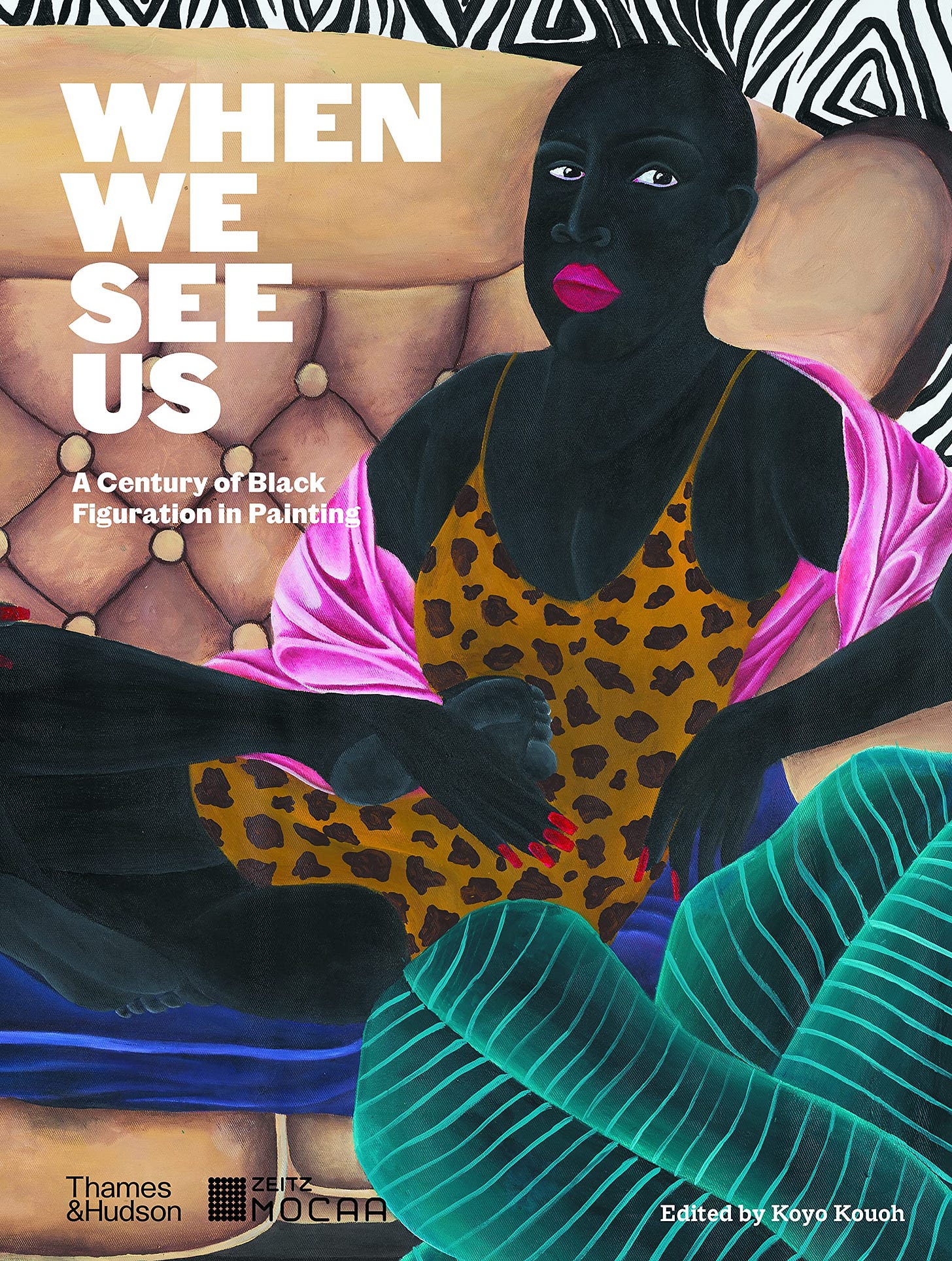

After setting up Raw in 2008, Kouoh would bring pieces of what made it special to her other high-profile engagements—she was involved from the beginning of 1-54 and become the second curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA), in Cape Town. The former is a celebrated contemporary art fair, and the latter a museum launched so recently before her accession to its leadership that she might as well be considered its founding curator. In each case, she brought a little of the special sauce she developed in Dakar: a curation not just of the art of “black geographies,”10 but of the conversations sparked by that art. Reflecting back on her role in the creation of the 1-54 Forum, Kouoh said:

During my time, Forum was running for three days at least and I think my position and engagement with reflection, analysis, and conversation is known, so that in this sense there is one side of enjoying the art but there is another side about understanding the art and where it is coming from. I am very interested in the process as most people know, so I am actually more interested in the artist’s head or the curator’s head or even collectors’ heads, than the art itself. This is really where it becomes interesting; where you really have the flesh, the meat, the spirit, and the details of what motivates and animates someone to make art, to curate art, to collect art. Hence the conversations are absolutely important and absolutely integral. On the other hand, for non-professional audiences, a conversation is also a stepping entrance or an entry to understand what all this is about actually. I think that the conversational and critical space is key and this is one of the conditions I made when Touria [El Glaoui] approached me—that I can have that space.

The revolution will not be illustrated.

Kouoh had arrived in Senegal during the presidency of Abdou Diouf, the hand-picked successor of founding president Léopold Sédar Senghor.11 A few years later Abdoulaye Wade was elected the country’s third president, marking the first transition of power to the opposition. By that time, Diouf had been in the executive mansion for nineteen years. Wade passed a new constitution, which after two terms and nearly twelve years in power, he sought to amend to make it harder for him to be defeated. In 2011, at the same time as the Arab Spring that Kouoh would long stress was also an African Spring, several overlapping protests against Wade broke out in Dakar, with the most prominent being Y’en a marre—“Fed Up With It.” In 2012, after a near run through successful public protests and two rounds of voting, Wade was defeated by Macky Sall.12

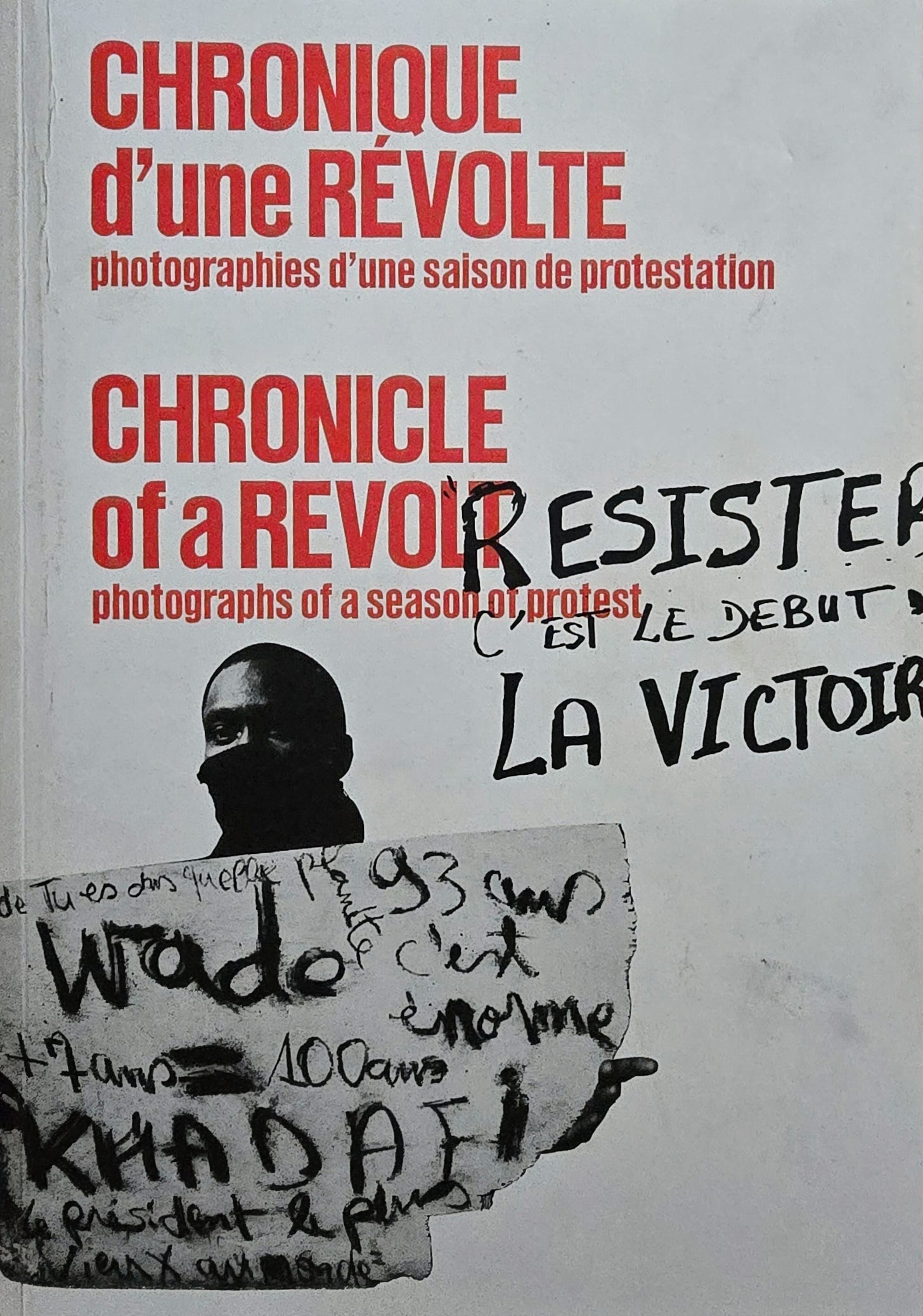

Raw gathered together two years of photographs by Senegalese and a few foreign journalists in an exhibition, also publishing them in book form just before Sall’s inauguration in the thick, glorious Chronique d’une révolte. There is a clear sense in almost every image of the photographer being fully embedded in events, surrounded by them. The pictures are sometimes beautiful but rarely aesthetized. While the book comes with a glossary explaining local terms—mbalax is “Senegalese popular music”!13—the photos are generally self-explanatory while also being most eloquent to viewers who bring the richest relevant experience to their perusal. In the 2025 Next Is Africa interview, Kouoh said of her approach in general, of which Chronique is a shining example:

The Western world loves dichotomy, binarity. Fortunately, I come from a culture where these notions have no place. It's not my role to correct the dominant narratives, the Euro-American shortcomings, or to fight against Western cultural myopia. It’s not for me or my community to do so. My work is guided by the urgency of expression and preservation. It's a quest for multiplicity, for nuance.14

This places Kouoh’s project in the same conceptual lane as the mainstream of African philosophy, discussed in the third post here at the Radical Cape Reading Room. While Kouoh, Raw, and Sarr might engage quite forcefully and relentlessly in such things as the fight for the restsitution of cultural artifacts held in museums in Europe, this is a choice, and in no way implied that they accepted the idea that what happens in Europe determines what matters in Africa. Kouoh, Raw, and their collaborators, like the African philosophers, are engaged in the tricky but rewarding simultaneous efforts to liberate the idea of Africa from Euro-American shackles and to build and develop that idea of Africa without it being durably shaped by the European and American constraints that once hemmed it in.

Kouoh’s project did not end there, however. While the political subfields of African philosophy range across the partisan spectrum, that of Kouoh and Raw tends to situate itself on the radical end of things. So doing meant for both artists and critics a certain exposure to pressure: pressure to align to particular radical orthodoxies, even though enforcement of orthodoxies of any kind can be inimical to intellectual freedom. Kouoh managed this difficulty by opposing prior constraints on Raw’s critics and artists, even when the constraints in question were coming from a radical position. She consistently spoke about this freedom that she helped to preserve for artists and critics as a freedom not to “illustrate” radical ideas. As she said about the Raw Material Company when interviewed by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage:

So I think artists, and certain artists and those we are interested in and we’ve been working with over the past few years are people that have in themselves created their own universes that have a response and have embedded in it political concerns, social concerns, and so on. And not in an illustrative way, but in deconstructed, even subversive ways that are challenging to the society. So, that said, as an art organization, you, especially in the context and the territories and the environment that I work with, you cannot not be hands-on, because you wake up in the morning, you open your door, you’re faced with issues. You cannot look away.15

This is far from a permanent recusal from political response. Given that much art and cultural criticism builds on foundations within Marxist humanism, whose sympathies occasionally spread quite a distance from the people Frantz Fanon sympathetically called The Wretched of the Earth, there remains the constant threat that the activities and populations with which such art or criticism aligns could wind up fairly irrelevant to people with the most pressing spark for liberation.

But part of the genius of Kouoh’s favored approach is in recognizing that prior restraint on critical thought and creativity is counterproductive no matter what its motivation may be. There will be plenty of time to measure out with coffee spoons the pros and cons of what has been created. We know that plain illustrations of pre-existing ideas are bound to be flat, with little meaning in and of themselves. So Kouoh, as interested as she is in creating a space to support those close to conceptual revolutions, insists: the artistic and critical contribution to the revolution will not be an illustration.

Footprints.

This post, looping as it does again and again back to Senegal, does not do justice to all of the different and productive ways that Kouoh’s interests were broad, ranging from Romaire Bearden to video installations to xeroxed prose-poems to getting the sculpture on the plane to government archives to fascinatingly minute reflections on the critical implications of mangroves in and beyond the work of Maryse Condé and Edouard Glissant. I apologize if this version of the story comes across as more parochial than Kouoh and Raw ever were. They ranged far and wide.

The temporal and processual structure of the Raw Material Company gave it a quantum of durability from the very start. As Barois de Caevel noted, Raw and Kouoh were in many ways one and the same, and making Raw last as part of the global reach of Kouoh’s critical ambition was a key part of her life’s work. The work was to her what Second-Class Citizen was to Buchi Emecheta and what The Color Purple was to Alice Walker. When Kouoh was named curator at Zeitz MOCAA in 2019, she set up a succession plan at Raw. Of course, the funding envelope everywhere is constantly changing, so only the long term will tell how that turns out.

Increasingly as the years went on, Kouoh would talk about her legacy, not with hubris, but with a sense of it being something for which she hoped to prepare. When she died after having been named lead curator of the Venice Biennale, but before the Biennale took place, there was a sense of suddenness to the news.

And it was sudden. Death is the dinner-guest who does not knock. Yet Kouoh was looking ahead as much as she could. Though not talking broadly about the cancer that would ultimately take her life contributed to the general sense of surprise her obituaries sparked, it also left her with a certain freedom of movement, freedom from being questioned, freedom from being required to illustrate certain ideas of the boundaries between life, death, work and legacy. She could build clear pathways that others would eagerly follow.

After the initial news of her demise had spread, the Guardian published an article Kouoh had written and embargoed shortly before, in which she talked about her vision for the Biennale. The curatorial team that she had put together delayed the announcement of the Biennale’s theme, which had originally been scheduled for 20 May 2025, which would have been ten days after she passed away. Instead, they gathered onstage one week later, flanking a video of her, to announce, as Contemporary & magazine put it in a headline, that the “Venice Biennale 2026 Will Folllow Late Koyo Kouoh’s Vision.” In the words of the Biennale’s own press release:

With the full support of Koyo Kouoh’s family, La Biennale di Venezia is committed to carry out her Exhibition. It will do so by following the project just as she conceived and defined it, with the further purpose of preserving, enhancing and widely disseminating her ideas and the work she pursued with such dedication to the very end.

Koyo Kouoh had a vision that was much bigger than her, and she built the tools needed to achieve it, setting them in front of skilled teams whose capacities she knew and trusted. Now it is up to those who support that vision or are intrigued or provoked by it, to make sure that “the very end” is not yet here, that the dead need not be dead—the dead have never gone away.

See, for a broad and slightly random sample of obituaries: the Manchester Guardian; the Johannesburg Mail & Guardian; the New York Times; the BBC; CNN; ARTnews; Hyperallergic; the Conversation; TrustAfrica; and Black Enterprise.

Sembène’s name is often rendered Sembène Ousmane. In keeping with other names found here, Senegalese and otherwise, this post places his surname last.

These articles and others are contained in Wainaina’s posthumous collection How to Write About Africa.

(Barois de Caevel in Barois de Caevel et al., eds. 2020, p. 120eng) The book is paginated from 1 to 167 in English and to 179 in French, reading inward from opposite covers.

Kouoh’s extensive bilingual English/French monograph on Samb, Parole ! Parole ? Parole ! which was published in 2014 and which I have not had an opportunity to consult, is the definitive record of this artistic and critical collaboration. In many ways, the history of the relationships Kouoh and Samb built are an art-scene corollary to David Byrne’s thesis on “How to Make a Scene” from his How Music Works. The Raw Material Company would be central to this effort. Samb passed away in 2017.

(Barois de Caevel in Barois de Caevel et al., eds. 2020, p. 121eng)

Senghor and Diouf’s partisan affiliation was to the Socialist Party, which was despite its name pursued a consistently pro-American centrist line in foreign policy, opposing, among other movements, the political pan-Africanisms of Gamal Nasser, Kwame Nkrumah, and Julius Nyere. The gap between the Senegalese socialists’ apparent politics and their actual politics had been at the heart of Aoua Keïta’s politely chilly reception in 1951.

Judd Devermont, advisor to American presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden, recently wrote, “I also had been frustrated by my own experience during the Obama Administration when we privileged leaders, namely those who—in a specific moment of time—were hailed as ‘democracy darlings.’ (That breathless praise, by the way, rarely passed the test of time. See Macky Sall of Senegal, for example.).” See:

(Kouoh, ed., 2012. vol 1, p. R70)